John Lancelot Burn, whose career and expertise were outlined in an earlier post, was the Medical Officer of Health in Salford. His 1950 Annual Report was an unambiguous call for the improvement of housing conditions in Salford. It was so convincing and significant that it was mentioned in the 1952 Twenty Year Development Programme for Salford as a catalyst for planning the wide-ranging slum clearance and redevelopment that would lead to the demolition of many terraced streets in Salford during the 1950s and 60s and the building of tower blocks to replace them.

We have smoke polluted air, more houses to the acre than almost anywhere else in England ... our new housing needs are as great as any other authorities, yet at least three-fifths of houses show evidence of rapid increase of decay. Over two-fifths of our houses have not those elementary physical requisites of modern child care and healthy family life – the provision of hot water, a properly ventilated food store accommodation and a fixed bath. But we have a cheerful hardworking people. John Lancelot Burn, Medical Officer of Health, Salford, 1950.

Burn, related to the unsanitary, overcrowded and unhealthy living conditions in most chapters of his report. Among them, tuberculosis was discussed at length as the rate of tuberculosis in Salford was high in comparison to the rest of the UK (0.51% in Salford – 1050 patients with pulmonary tuberculosis, among them 500 were infectious, 121 deaths were caused by the disease – vs 0.36% in the UK).

To reinforce facts provided in statistics and learned via medical practice, Burn added to his report examples of patients, living in overcrowded conditions with children under the age of 15:

Father (tubercular) wife, brother and son (4 years) lodge with aunt (tubercular) aged 61 years, and grandmother, 83 years. Maternal grandmother died from pulmonary tuberculosis. Mother and the child sleep together in a bed, and father sleeps in a bed chair in the same room which opens into the bedroom occupied by the aunt, who sleeps with the mother. There are three bedrooms plus one living room which is shared by the whole family. The front room is used as a shop (p. 10).

Such examples served Burn in showcasing housing conditions and overcrowding as causes for the high rate of tuberculosis because family members living in such conditions were infecting each other. To prevent infection, Burn argued for essential improvements and described the ideal home situation:

... to have a separate bed in a separate room [for the patient with infectious tuberculosis] and sufficient additional accommodation for the remaining members of the family, as it is absolutely essential that contact with the case should be reduced to a minimum (p .9).

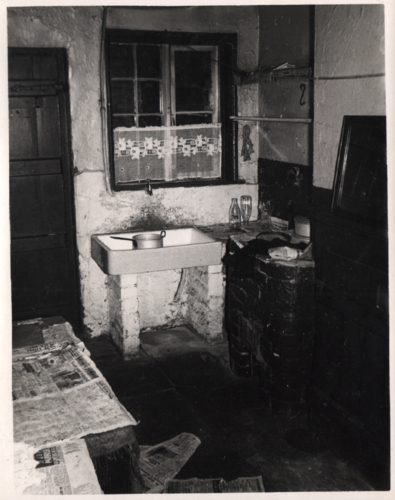

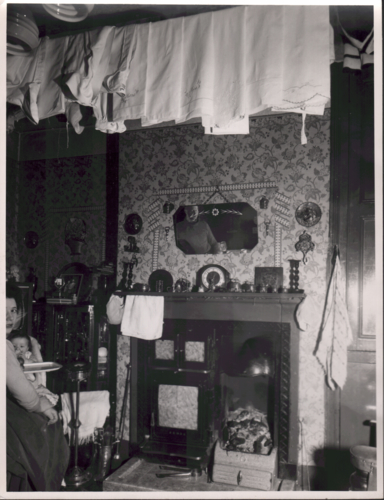

This ideal was, sadly, not attainable in Salford at that time as most households lived in overcrowded conditions and with inadequate cooking facilities that made it difficult to sterilise sputum cups and crockery.

To improve the situation, the Housing Committee had increased allocation of housing for families affected by the disease but Burn warned that this was not sufficient: “If at any time we become complacent about the problem of housing, our postbag with its pathetic appeals would quickly set that right” (p. 5). It is telling that Burn didn’t provide additional information on how much more housing was provided, and to how many families, or how much more housing was needed just for those affected by tuberculosis. It can be assumed that this was the case only for some of the most extreme cases and probably in modest quantities.

Burn’s report makes obvious and clear connections between the necessity of ‘slum clearance’ and the high rates of tuberculosis and he continued to return to the topic later in the same report. Without mentioning tuberculosis explicitly, the poor housing conditions are related to health:

We are irked by the futility of our daily endeavours to patch up and prolong the life of worn out and obsolete houses: a considerable bulk of the dwellinghouse property in Salford is a liability from everybody’s point of view. Desperate ills call for desperate remedies: in embarking upon a programme with the ultimate object of making Salford a City fit to live in, the Council must be ruthless in dealing with the properties which so ill serve the domestic needs of the people (p. 7).

What is suggestive in this statement is the use of words such as ‘obsolete,’ liability,’ and ‘ruthless’ as they remove any value from the existing housing and appear to foreshadow the radical nature of demolition and redevelopment of the 1950s and 60s.

Another argument, put forward by Burn was the effect of inadequate housing on the mental health of citizens. Here too he used testimony to strengthen this argument although some examples are of social rather than psychological nature:

Living in two front rooms, one up and one down: no cooking facilities except parlour fire, all water must be carried: sleeping in two beds (no room for more). Children healthy, well fed and well clothed, but mother on the verge of depressive breakdown aggravated by fact that husband understandably spends as little time as possible in the home (p. 8).

Daughter, aged 22, was away in service. About two years ago she was home-sick and wished to come home, but mother had to refuse owing to lack of room. Daughter recently returned with illegitimate baby which must be considered as largely the outcome of her enforced isolation from home (p. 8).

Much of the report returned to the housing conditions as cause for a range of ailments in health and society: Tuberculosis was exacerbated by overcrowding, men frequented the public house as a way to keep away from their small homes, and women became depressed and overwhelmed as a consequence of inadequate homes.

Such cause-effect relationships had been assigned to poor housing conditions since the 1920s. They also had since that time been intrinsically related to modern architecture that was put forward as the opposite of slum housing. Modern architecture had – since its inception – been promoted as providing residents with ‘healing’ environments because it was hygienic and would prevent tuberculosis. It also had been assigned as capable of remedying ‘social disease’ as it provided more luxurious environments – hot water, heating, etc. – so that families would be enticed to spend time together peacefully and happily.

It would be another 15 years before the University of Salford would launch a survey with tenants in ‘high flats’ to investigate whether or not such ideologies had come to pass. This, survey, will be the topic of another post.

The images in our blog post were taken from Digital Salford that is part of the collections of Salford Museum and Art Gallery. These images were gifted to the museum and the original owner is not always known. If you are the copyright owner of an image, and if you would like to tell us more about it, please contact us. Please also contact us if you would like us to remove your image: themodernbackdrop@salford.ac.uk