Let us, however, be far sighted in our plans and not discard the desirable for the attainable – that which is right for that which is expedient. S. C. Hamburger Chairman of Building and Development committee, February 1952.

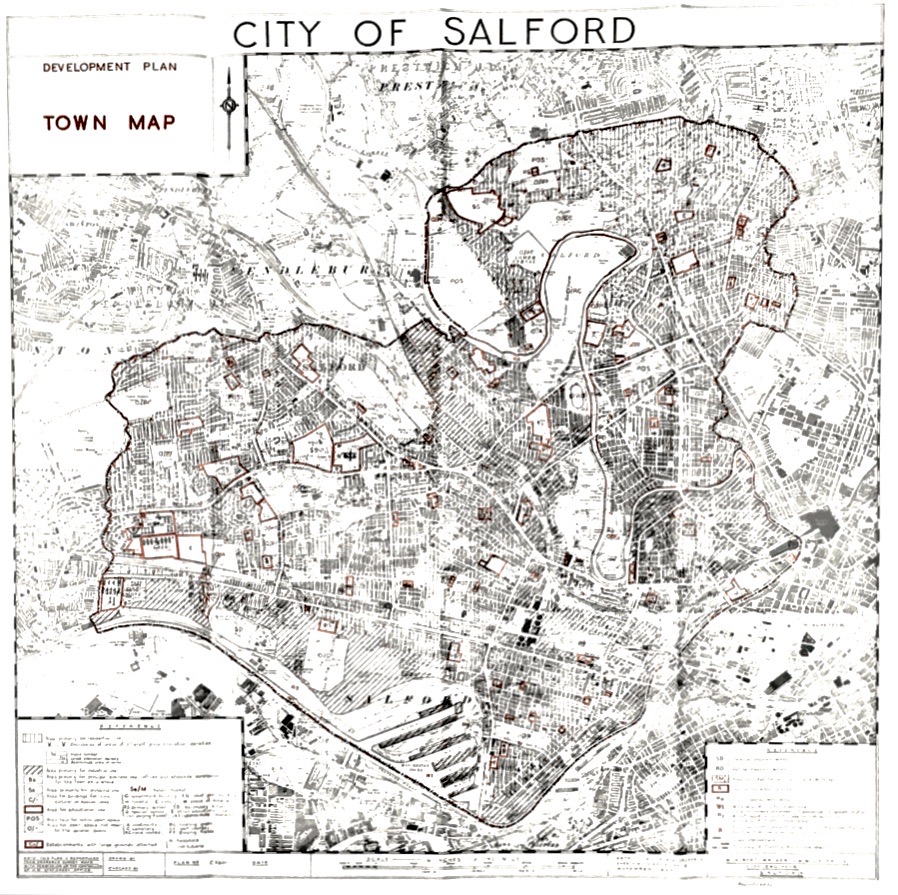

In 1952 the City Council published the abridged version of its 20-year development plan drafted by the former city Engineer W. A. Walker. The plan set into motion a slum-clearance and development initiative that had been discussed for a long time. Now, a clear agenda and goals were published. This is a reflective reading of some parts of this plan with the goal to understand the ways of thinking about the status quo of housing and urban areas that might have underpinned the decision-making of planners, architects, and the council in subsequent years.

Much of the document consists of a survey of Salford, its history, geographical features, urban condition, etc. and provides readers with a range of quantifiable data:

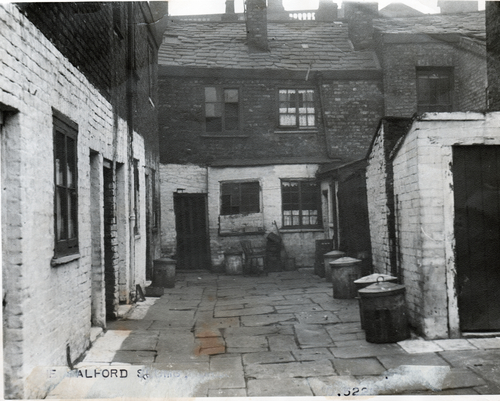

Population in December 1950: 179,234 Rateable value: £1,138,593 City Area: 5,202 acres Public and privately owned open space: 734 acres (14%) Number of houses: Approx. 52,000 covering 2,240 acres of the city More than half of these houses were built before 1890 Urban density: more than 40 houses per acre Houses in poor condition and to be ‘cleared’ in the next 20 years: 12,355 Persons in need of ‘separate accommodation’; i.e persons on waiting lists due to overcrowding: 9,500

Problems outlined in the report

Several planning problems or rather “deficiencies and defects” were found within Salford. Among them, the urban density and the proximity of housing and industry was given heightened attention – probably because of the conundrum that new housing was needed but at the same time industrial enterprises in Salford needed to be considered during the redevelopment process. It was not possible to remove existing industrial premises instantly which hampered redevelopment as new housing would have to be built around existing industrial premises. To resolve this problem a zoning plan was proposed that would – over time – separate houses from industry.

The railway too was seen as a barrier for improvement because its ”immovable features hamper redevelopment of a largely obsolete area of the City” (p. 7) but it is not made clear in the report which areas in particular are referred to (train tracks, railway buildings, etc).

The lack of a city centre and urban focal point too was pointed out, and that Manchester’s shopping provision deducts attention from Salford. Therefore, the city “suffers a psychological as well as a physical deficiency” (p. 7). While the economic consequences of this lack of an urban centre are indicated in that shoppers go to Manchester instead of remaining in Salford, the nature of psychological and physical deficiencies are not clarified and left to the interpretation of the reader.

Another problem identified in the report was the lack of open space in some parts of the city. Redevelopment of the most congested areas was planned but open space was thought of as only possible to increase with the help of “overspill of population to other areas” (p. 7). Part of this point was also that there was a lack of playing fields which could only be remedied if dwelling-houses were removed.

Flooding of the river Irwell was the final planning problem discussed in the report but regarded as within the responsibility of the Mersey River Board.

Proposed solutions

“Clearance of the dense and unhealthy areas which form a high proportion of the south-east and central areas of the City” would bring solutions for these six planning problems. When carrying out this task, new challenges were made aware of as “tenants dispossessed of their homes ” (p. 7) had to be accommodated and lower densities would replace overcrowded areas leading to a “mounting overspill of population.” (p. 7) The logistics of rehousing and overspill is also discussed in some detail as a main obstacle when carrying out the development plan.

In addition, some redevelopment activities had already commenced in 1952 in the Trinity and Islington areas at two not further specified sites that had been cleared due to war damage. Another 15 acre area was also planned to be cleared in Trinity Ward. When reading the report it is not quite clear if the terms ‘clearance’ and ‘redevelopment’ delineate different concepts or are used interchangeably. ‘Clearance’ delineates the demolition of housing whereas ‘redevelopment’ could be understood to indicate a more complex process: the demolition of housing, the planning of new housing, and the building of improved housing. It appears that ‘redevelopment’ was used in an aspirational sense in that the steps after demolition were already being considered but had not yet taken place or considered in detail.

Another significant part of the plan was the assessment of historical value of existing buildings: “in Salford [there are] no scheduled ancient monuments […] and no structures of great antiquity” (p. 8). Buildings of architectural and historic interests were ten ‘Class II and seven ‘Class III’ buildings, all of which were planned to be retained. Among them were Kersal Cell, Bexley Square Town Hall, Ordsall Hall and the Independent Chapel on Chapel Street. This selection of buildings of ‘architectural and historic interest’ is of course highly subjective and very much a reflection of 1950s understandings of value and quality. Buildings with religious, political or age value were mostly considered as worth-while preserving as they were reflective of a historic, political, and socio-economic development over long periods of time. To preserve examples of housing, public houses or shops which were deemed parts of ‘slums’ would have not been considered by stakeholders at that time. However, the plan does not make mention of the small-scale housing developments built since the end of the Second World War. Among them were a number of prefabricated dwellings. To demolish these was not surprising as they had been built to only last approximately 10 years. We have introduced to some of these ‘prefabs’ in earlier posts. Other housing, however, had been relatively new in 1952.

The “Housing Need” was determined from several observations and findings. About 25,000 houses had been built before 1890 and produced an urban density of more than 40 to the acre. All of these houses were to be replaced. During the next 20 years, the plan was to replace 12,355 houses on the most “obsolete areas” (p. 9). This number was based on John Lancelot Burn’s Slum Clearance Programme and on his findings.

In a table the total sum of houses to be demolished was calculated as 33,560 which affected approximately 114,164 residents. When reading the table, not all information that would be needed to fully appreciate the significance of it are provided. Burn’s report is taking into consideration but other items in the table e.g. ‘individual loss’ and ‘less voluntary migration’ (4,200 residents) are not outlined in detail.

When outlining the ‘Estimated House-Building Capacity” it was estimated on the assumption that 360 houses would be built per year: 12,025 houses in twenty years.

The programme goes on to discuss planned roads, utilities and social services (mainly schools) and finishes with a written statement by the Minister of Housing and Local Government that summarises the plan and adds some additional information on, for example, the proposed zoning plan and the population development.

The final page of the programme shows, with the help of a table, which areas of Salford are planned to be developed, in which time-scale, and how many houses will be removed, replaced and how much overspill housing will be provided.

The plan is based on a survey and on six ‘major planning problems.’ The basis for the survey, i.e. the parameters with which a house is declared a ‘slum house’, or contextual information about obsolete areas in relation to the railway, are not made explicit. Some tables, such as the ones describing the housing need (p. 9) and house-building capacity (p. 9) also lack context. No legend or explanation that help understand these numbers is presented.

In addition, the programme does not argue for the necessity of the development plan. It states facts and figures but does little to interpret them or to contextualise them so that the necessity and logic of the programme becomes apparent to the reader. It seems that the numbers were left to ‘speak for themselves.’ In addition, the number of houses planned to be built is ascertained but the type of architecture is not which seems to indicate a vagueness in the term ‘house’. Rather than ‘houses’ – ‘dwelling units’ seemed to have been meant which later appears – at least in part – to translate into the word ‘flats.’