Conference at the University of Salford, UK, 25th-26th May 2023

Venue: Peel Park Campus, Chapman Building, Lecture Theatre 4

The development of social housing estates after the Second World War in Europe initiated in many cities the radical transition of urban environments. The plans and hopes of architects, planners, and city councils not only focussed on elevating living standards; modern housing estates were also believed to support the development of ‘new communities’ within which pre-existing and widespread social problems would dissolve.

Such modern developments appear in the material and visual culture (film, TV, art, literature, newspapers, etc.) between the 1950s and 1960s whereby artists observed and commented on the transition of urban quarters from blackened, often decaying 19th-century houses to modern tower blocks. The lives and living conditions in the old and new working-class quarters interested artists, filmmakers, and writers as much as the aesthetics of modern urban quarters. Both provided the backgrounds for commentaries on changes in society and modernisation. Movies such as Albert Finney’s Charlie Bubbles in 1968 or Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 A Clockwork Orange utilised the imagery of this transition and offered commentary on the effects and social consequences of modernisation. Kitchen Sink Dramas such as Coronation Street (1960 – ) in the UK, also addressed social housing and modernisation efforts. The literary work of J.G. Ballard (High Rise, 1975) and B.S. Johnson (The Moron Made City, 1966) react to urban modernisation satirically and critically. In the fine arts, the topic and its social consequences were addressed multifacetedly; photographs by artists such as Shirley Baker, UK and Albert Renger-Patzsch, Germany juxtapose social housing and its inhabitants who appear alienated from the modern environment they find themselves in. Representatives of Art Brut and Art Informel were inspired by non-traditional subject matter and art production that was perceived as more genuine. Artworks such as Jean Dubuffet’s Parages fréquentés (Busy Neighbourhood), 1979 observed the asphyxiating nature of urban spaces. Others considered emotional conflicts, society and its development after the Second World War. Yuri Pimenov, on the other hand, worked in the context of the Soviet Union (Wedding on tomorrow’s street, 1962) and depicted the modernisation of cities and social housing as a beacon of hope and evidence of the improving living conditions of the working class.

Conference Schedule

Venues

Chapman Building, Conference Venue

Working Class Movement Library – Venue for the Film Screening on Thursday, 25th of May and the Shirley Baker Exhibition (visit on 26th of May)

Salford Museum and Art Gallery – Venue for Lunch on Thursday, 25th and Friday, 26th of May and guided tour Lark Hill Place exhibit.

Salford Student Union and Atmosphere Bar – Conference Dinner on the 26th of May

Abstracts and Biographies

Keynote

Miles Glendinning, Urban Modernisation – the Global Context: State intervention, modern architecture and ‘slum’ clearance across the world

Abstract

Complementing and contextualising two earlier contributions to the Modern Backdrop project, this lecturer explains how state power and modernist architecture interacted to produce a kaleidoscopic diversity of approaches to planned urban modernisation across the world in the post-war era.

Contrasting somewhat with the continental European modernisations covered in my previous lecture, with their emphasis on vast ‘grands-ensembles’ on city peripheries, and their relative lack of interest in inner-urban clearance – as distinct from reconstruction following wartime devastation – this lecture homes in on inner-urban slum clearance, the core focus of the Modern Backdrop project.

It argues that slum clearance was a special preoccupation, or speciality, of the Anglophone world, which featured an especially aggressive, slash-and-burn approach by ‘Authority’ to the management of earlier urban environments. Here, too, however, there was kaleidoscopic variety in the types and terminologies of intervention – for example within ‘First-World’ Anglophone countries, ranging from US ‘urban renewal’ and British/Irish ‘slum clearance’, to Australian ‘slum reclamation’. But more surprisingly, the same formula also then jumped dramatically to modernising, decolonising regimes in very different, East Asian urban contexts, in the city-statelets of Hong Kong and Singapore, where it became associated with clearance not of 19th-century industrial urban legacy zones, but of informally built shanty-towns and squatter-settlements, and resettlement of their occupants into ultra-high-density, and ultimately ultra-high-rise, redevelopments of highly diverse kinds. Those programmes still continue in full force today, generally untarnished by the stigmatisation and reputational collapse which has affected many of their western predecessors – not least in Salford.

Miles Glendinning is Director of the Scottish Centre for Conservation Studies and Professor of Architectural Conservation at the University of Edinburgh. He has published extensively on modernist and contemporary architecture and housing, and on Scottish historic architecture: his books include the award-winning Tower Block (with Stefan Muthesius), The Conservation Movement, and Mass Housing – Modern Architecture and State Power – a Global History (Bloomsbury, 2021). Other planned books include a history of public housing in Hong Kong (Routledge; likely publication 2024) and a history of postwar housing in London.

Session 1: SYSTEMS

Stephen Lovejoy, The French Connection: The Sceaux Gardens Estate and the promise and peril of bringing L’Esprit Nouveau to south London

Sceaux Gardens Estate, London. Photo: Stephen Lovejoy, 2019.

Abstract

The first industrial revolution covered the ground with asphalt and bricks. The second is uncovering the ground and discovering the sky.

‘The Changing Face of Camberwell’, 1963

Sceaux Gardens is an estate of 400 council homes built in the 1950s to replace war-damaged terraced homes and factories in north-east Camberwell in south London. The estate was named after the Sceaux suburb of Paris and each housing block was named after a prominent French figure, but the influence didn’t stop there. Unusual for a London borough, Camberwell had an architect’s department, led by F. O. Hayes. The department designed Sceaux Gardens in line with ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’ principles of French modernist architect Le Corbusier.

This approach was a reaction to the perceived shortcomings of working-class homes, which were overcrowded with a lack of light, sanitation, and green space. The housing blocks were designed with prefabricated components and modern materials and techniques. Single-storey bungalows were interspersed with six-storey and fifteen-story blocks. To maximise views and daylight maisonettes were designed in a ‘scissor’ arrangement, with the upper storey crossing the building to include windows on both sides.

My research is centred on the reasoning and reception of this new approach. Part of a wider wave of new council housing built in the area, Sceaux Gardens is an example of some of the opportunities and shortcomings of bringing ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’ to south London. Contrasting yet complementary to its surroundings, the estate was included in an eponymous conservation area less than a decade after its construction. In 1960 The Architects’ Journal described the design as “the most interesting housing scheme to have come from a Metropolitan Borough Architect’s Department,” but also raised prescient questions about the fire-safety of the tall blocks. The light, privacy, and modern conveniences were praised by residents, but they also had concerns that the designs might act as a barrier to sociability. The estate captures the question of the extent to which the dismissal of the housing of old paved the way for a new future or replaced one set of a problems with another.

Stephen Lovejoy is an ARB-registered Architect and Urban Designer with over 7 years of professional experience working across projects in the UK and China, specialising in housing, heritage-led regeneration, and town-centre recovery. He is a Senior Lecturer at London South Bank University, where he teaches Architectural History and Theory. He is also an Urban Designer and Planning Officer at the London Borough of Southwark, where he is responsible for producing Area Character Studies. This involves researching the past and present of neighbourhoods in the borough and engaging with the community to guide how the area should change in the future.

Alison Davies, Bursting the Balloon: from rise to fall in 18 years

Demolition of Balloon Wood, 1984. Photo: John Birdsall / Alamy Stock Photo.

Abstract

Balloon Wood in Nottingham was a modern, medium-rise, deck-access housing estate built in the 1960s to re-house ‘slum’ dwellers from other parts of the city. It was a prototype of the system developed by the Yorkshire Development Group (YDG): a collaboration between Nottingham, Sheffield, Leeds and Hull City Councils. Conceived by architect Martin Richardson as a flexible, modular arrangement of generously-proportioned interlocking units, a construction system of structural concrete panels was agreed with The Shepherd Building Group for its delivery.

The cleverness of the system was celebrated in a short promotional film entitled Community Builder in 1968 – complete with a groovy 1960s soundtrack – promising homes “as up to date as the mass-produced goods inside them.”

The Architectural Review gave it its endorsement in a special housing issue from 1970: “of all the building systems hastily foisted on housing authorities in the mid 1960s, YDG stands unique. Its starting point was the family – the dwelling conceived as the unit.”

Designed to house two 2,300 residents Balloon Wood was one of Nottingham’s most ambitious post-war housing projects. Phase one comprising 23 interconnected blocks, was constructed between 1966 and 1970. However, soon after it was occupied, the cracks in the system were literally and metaphorically beginning to show, with tenants complaining of building defects, damp and mould.

The decline was so swift that the planned second phase was cancelled. In 1982 Central News was reporting on the tenant-led campaign to be rehoused, and the estate was cleared and demolished by 1984. Hence the ill-fated experiment lasted less than 20 years at considerable cost of displaced community and wasted carbon.

This paper explores the short-lived fortunes of Balloon Wood, with reference to national and local media representation, and first person testimony from former residents.

Alison Davies RIBA is an assistant professor at the Department of Architecture and the Built Environment at the University of Nottingham UK, where she runs architectural design studio unit 5A. Her research interests include the post-war New Towns movement, social housing, and the definition of territory in the public realm. She is also an award-winning architect in practice, and founder partner of Nottingham-based Urban Fabric Architects.

Tanja Poppelreuter, Yudishthir Shegobin, Sunshine Ghetto: Histories of Territorial Stigmatisation at Hulme Crescents, 1965-2020

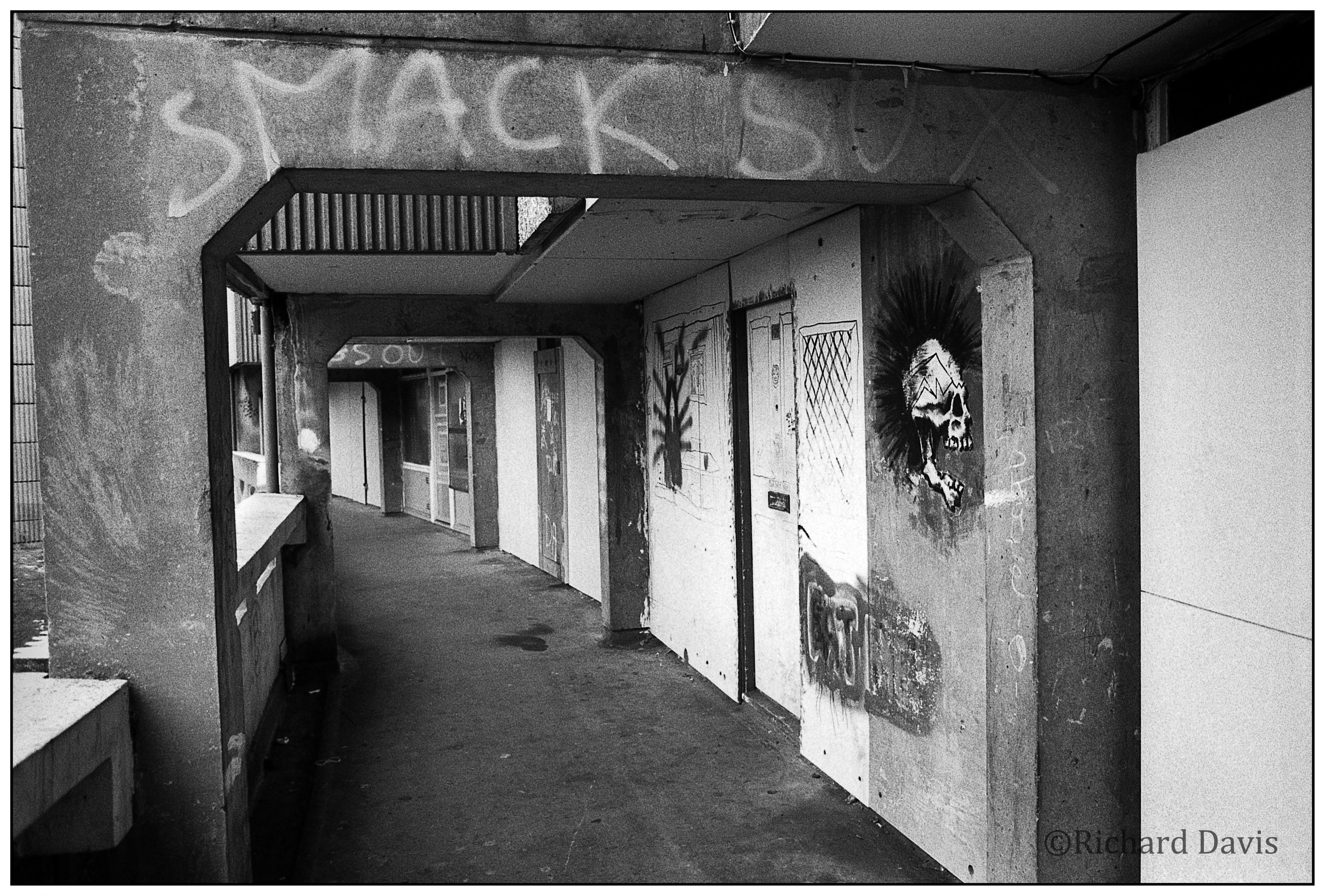

Richard Davis, Hulme Crescents, c. 1990. Photo: Richard Davis.

Abstract

Territorial stigmatisation describes the site, causes and effects of stigmatisation that marginalised, low-income and minority groups in contemporary western societies experience. Such territories are located in urban contexts and often within social housing estates. The effects of territorial stigmatisation on residents have been amply discussed in recent scholarship that often applies this term to address failed attempts to ‘destigmatise’ social housing or to influence policy. While the role of the press as an agent that produces or maintains stigma is acknowledged, processes that create reputations and stigma across long periods of time are discussed to a lesser extent.

This paper addresses the changes in the reputation and mechanisms of stigmatisation on the example of the large-scale housing estate “Hulme V” or “Hulme Crescents” in Manchester that was built in 1968-72 and demolished by 1995. It aims to contribute to the discourse on contemporary advanced marginalisation by suggesting the inclusion of historical analyses of stigmatisation processes to this critical methodology. It can be shown that – by retracing the reputation of the estate from celebrated new community, to trash-filled estate inhabited by slum dwellers, to drug-fuelled urban Badlands and finally to the hotbed of post-punk creativity – stigma can be regarded as a fluid phenomenon that is changeable over time.

Tanja Poppelreuter is a Reader in Architectural Humanities at the University of Salford. Her research interests lie in the field of 20th-century art and architectural theory with a focus on the impact of politics, gender, exile, as well as space perception on these fields.

Her work shifts the attention from the architectural object to architects’ intentions of composing spatial experiences and to theories on the transformative capabilities of space on the human mind. Her latest publications consider the experiences of women with an education in architecture in exile. This research analyses the cultural and professional challenges associated with exile and draws on theoretical frameworks within gender studies and exile studies to suggest an alternative way of presenting historical events.

Yudishthir Shegobin is a junior architect in Mauritius. His M.Arch dissertation at the University of Salford, Manchester, discussed spatial manifestations of social exclusion at Hulme Crescents. His dissertation was presented at the ATUT Annual Symposium for Architectural Research in Tampere, Finland in 2019.

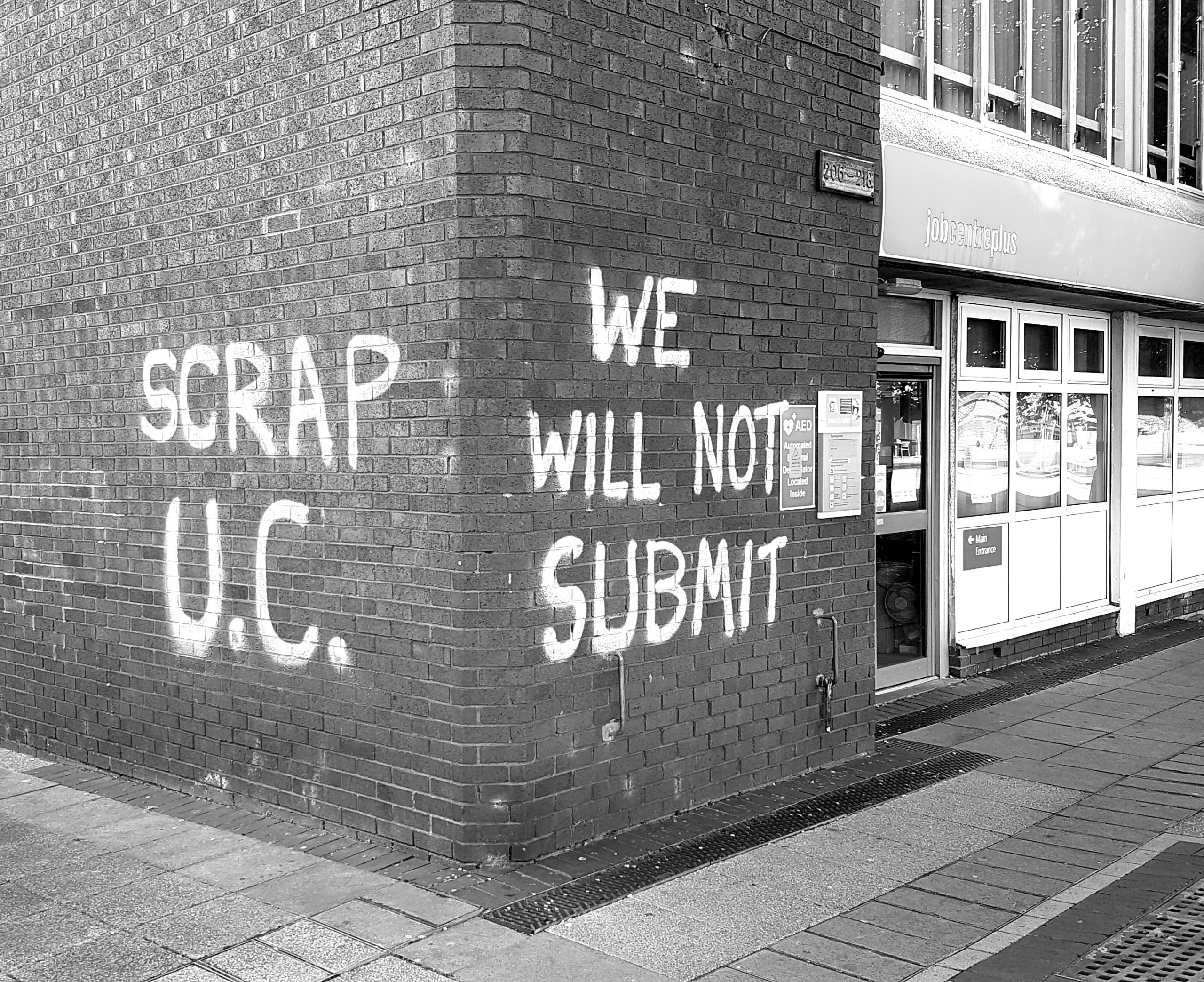

Colin Stuhlfelder, From the Respect Agenda to Universal Credit, challenging the Othering of Social Housing Tenants and Residents.

Graffiti on the Bootle Job Centre, Merseyside. Photo: Colin Stuhlfelder, 2019.

Abstract

Former US President George H W Bush once advised the American public they should be ‘a lot more like the Waltons and a lot less like the Simpsons’ in an attempt to draw family values closer to the rural ideal of one, compared to the suburban chaos of the other, regardless of the fantasy nostalgia of the former for a life most Americans had never lived in any generation.

Such judgements can be seen echoed in British representations of families, with the Simpson-esque role being filled by the Manchester estate-based comedy drama Shameless for the early part of the 21st Century. Like The Simpsons it became the target of political intervention over a Shameless – generation venerating stereotypes of – out of work, benefit claiming, substance abusing Council/Social Housing tenants, with these tropes being painted as the natural, inevitable and unavoidable result of life on such estates.

These expressions of life on estates, and their coalescence with concerns around the emergence of policies, for example, under the last Labour Government (New Labour, 1997-2010) to tackle anti- social behaviour through the blurring of Civil and Criminal law in the Anti Social Behaviour Orders they introduced, and the Respect Agenda policy, saw these interventions disproportionally targeted at Council/Social Housing providers and their tenants and residents.

From experiences working for a Housing Research project at the Manchester-based Ahmed Iqbal Ullah Race Relations Resource Centre, with a North Liverpool Housing Association, Cobalt Housing, and delivering CIH accredited Social Housing programmes to staff in the sector, Dr Colin Stuhlfelder will explore how notions of Othering tenants and residents has suited the political programmes of various governments, as well as exploring how these correlate with media driven stereotypes, and adapt to fit the demographics of different demographics and communities across the UK.

Colin Stuhlfelder is a new Lecturer in Architecture at the University of Salford, joining after 15 years at Wrexham Glyndŵr University where he started as a Lecturer on Chartered Institute of Housing accredited Social Housing programmes. He has a background in social housing design, research, on and working on the North Liverpool Cobalt Housing estates and is an avid Urban Explorer and photographer.

At Glyndŵr Colin was involved in directing Housing Strategy from the North Wales coast to the Heads of the South Wales valleys and in more recent years was recognised as a Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Architectural Technologists.

Session 2: Media and Visual Culture

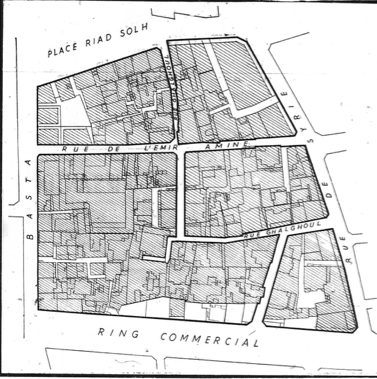

Jan Altaner, “‘Manhattan’ of Beirut”: Newspaper representations of working-class neighbourhoods in urban renewal projects in Lebanon, 1958-1975

Image: L’Orient, 27.03.1965.

Abstract

On March 27, 1965, Lebanon’s influential bourgeois French-language daily L’Orient proclaimed on its cover: “In 10 years, two leprous neighbourhoods of the city centre will become the ‘Manhattan’ of Beirut”. Aerial photographs showing the low-rise, densely built-up working-class neighbourhoods of Ghalghoul and Saifi accompanied the headline, juxtaposed with a model of skyscrapers in the international style that would replace them. As part of nation-building efforts between 1958 and 1975, this urban renewal project proclaimed to ‘modernize’ Downtown Beirut (Verdeil: 2010). In twenty articles, L’Orient enthusiastically propagated the project, representing the architecturally, socio-economically, and functionally diverse neighbourhoods as dirty, disorderly, and under-developed, thus stigmatizing them as intolerable slums. Drawing on newspaper records, urbanism plans, contemporary surveys, parliamentary debates and photography, this paper analyses L’Orient’s representation of the working-class neighbourhoods between 1958 and 1975 and the curious absence of questions surrounding the rehousing of its inhabitants, both in the project and its coverage.

Reconstructing the erased neighbourhoods’ history, I argue that their stigmatization by L’Orient as slums inherently opposed to urban modernity was central in popularizing and legitimizing their planned erasure. The newspaper never discussed the project’s exclusion of former inhabitants, their planned displacement, or alternative housing options, which points to a larger, unexplored theme in Lebanon’s modern history. Indeed, despite the availability of resources and trained experts, and the public awareness of a severe, on-going lack of affordable housing, hardly any social housing was constructed. I argue that the absence of rehousing discussions in L’Orient reflects a general lack of concern and responsibility among Lebanese politicians and society’s upper strata to provide social housing to Lebanon’s urban poor. This paper thus contributes to the historiography of slum clearances, social housing, and the involvement of news media in the global 1960s beyond an exclusive focus on Western countries.

Jan Altaner is a PhD candidate in History at St John’s College and is supervised by Professor Andrew Arsan. He holds a BA in History from the University of Freiburg and an MA in Middle Eastern Studies from the American University of Beirut. Employing approaches of urban, social, and economic history, Jan’s doctoral project examines Lebanon’s political economy following the country’s independence in 1943 until the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War in 1975. It explores the role financial capital and banks played in transforming the Greater Beirut Area into a space for real estate investments, thus prioritizing the interests of richer over those of lower socio-economic classes and sheds light on Beirut’s marginalized inhabitants and how they navigated (and resisted) an increasingly unaffordable housing market. The dissertation aims to deepen understandings of the modern Levant’s political economy and urban history, to historicize the financialization and shortage of Beirut’s urban space, and to further scholarly approaches favouring class- over sectarian analysis in Lebanon and MENA more broadly.

Aleksandar Vujkov, Representations of Labor and Work in the Early Films of Želimir Žilnik

Crni film (Black Film), Želimir Žilnik, Yugoslavia, 1971, Film Still. Source: https://www.zilnikzelimir.net/index.php/black-film, accessed April 24, 2023. Image Credits: Želimir Žilnik, Neoplanta film.

Abstract

Thematically broad, covering social phenomena as seemingly diverse as unemployment, sexuality, homelessness, Žilnik’s early work, from the mid-1960s to early 1970s, was a moment of ideological reckoning between normative aspirations of socialism in Yugoslavia and actuality of social practices. It was a diagnosis of troubling class dynamics, increased social stratification and rise in social inequality; in short, it mapped system’s many contradictions. Žilnik’s work gave legibility and public representation, indeed a voice, to socially excluded and culturally marginalized. In Crni film (1971) by portraying a group of homeless who are invited to Žilnik’s own apartment, Žilnik is critically self-reflective of his position, and social standing, questioning limits of director’s criticality. Fully cognizant of the artificiality of filming process, subjects are invited to perform and testify their lived experience, making process of construction of social and cultural identities legible, while challenging limits of the medium and process of film making as, after all curated, by the director. Beyond passive reception, these films invite cognitive confrontation with social logic of subject’s position.

The occurring theme is a process of exclusion of socially and culturally underrepresented groups (in socialist Yugoslavia, access to political sphere was legitimized through labor, work and employment status), but also their own vitality, capacity to negotiate circumstances of the context, that is fundamentally inimical to them, despite official ideological registers claiming otherwise. These films investigate relationship between personal and political, individual and collective. Žilnik’s position moves beyond dissidence, his films are expressions of criticism, for their investigation of the limits and potentials of medium and conventions of authorship, but they are also critiques of the system from within, maintaining commitment to socialist project predicated on equality and social justice, they are a call for its change. Žilnik’s work was contextualized from number of standpoints, ranging from histories of displacements and migration, to changing content of worker’s self-management, its ideological narratives and social repercussions. This paper will investigate representations of labor and work in Žilnik’s films, and their many implied meanings, in a nominally socialist society that rested on production base that incorporated significant aspects of market economy.

Aleksandar Vujkov is a PhD Candidate (ABD) at the University of Illinois at Chicago, specializing in the history of architecture, design and urbanism; his dissertation investigates urbanization in socialist Yugoslavia.

Jakub Machek, Large housing Estates in Late socialist Czechoslovak Films and TV Series as an Exemple of Life in Socialist Society

Film Still: Věra Chytilová, Panelstory aneb Jak se rodí sídliště (1979).

Abstract

Although the mass construction of large, prefabricated housing estates began in Czechoslovakia in the mid-1950s, audiovisual production did not begin to focus on it fully until the 1970s, when this construction was also taking place at its greatest intensity. After the political, social, and media-related relaxation that took place in the 1960s, which reflected this construction only to a minimal degree, the new regime, established by the Soviet occupation in 1968, focused on entertainment genres representing an idealized, exemplary form of everyday life to promote the benefits of living in a socialist system. The presentation of the provision of modern housing for the growing population was one of the highlights of its propaganda strategy.

At the core of the proposed paper is a semantic analysis of several key contributions to the image of the housing estate in Czech audiovisual production, set in the period context of the functioning of society, the media and the systems that managed it.

In their essence, the two works depict very similar -even identical- scenes from everyday life in a housing estate complex in completely contrasting ways. The TV series Dnes v jednom domě (Today in a House, 1980) represents the creation of a vibrant neighbourhood community in a newly built block of flats based on the fates of families of different social backgrounds. The counterpoint is Panelstory (Story from a Housing Estate, 1979), which takes a critical look at life on a similar housing estate, depicting it as extremely anonymous and alienated. But tightly controlled media was dominated by positive propagandistic portrayals showing life on the new estates as helping to improve interpersonal relationships, in contrast to the old, bourgeois construction in the city centres such as such as shown in Zítra to roztočíme, drahoušku…! (We’ll Kick Up a Fuss Tomorrow, Darling…, 1976).

Jakub Machek is an Assistant Professor at the Media Studies Department, Metropolitan University Prague. He is the author of the monograph Počátky populární kultury v českých zemích [The Emergence of Popular Culture in the Czech Lands, 2017] and he has co-edited several collections of essays. He is also the author of several book chapters and journal articles. His latest research is focused on the function of music in Czech society, from brass band music to disco. He is a founding member of the Centre for the Study of Popular Culture in Prague.

Session Three: REDEVELOPMENT AND MOBILITIES

Jonny Smith, “I would love to go back to the old house, but I never will”: Re-examining Post-War Redevelopment & the Spatial Politics of Working-Class Identity in 1960s British Cinema

Film Still: Billy Liar, 1963.

Abstract

The significance of place has been integral to academic debates around working-class representation in 1960s British Cinema, particularly through the work of Andrew Higson (1984), John Hill (1986) and Terry Lovell (1990). While much of this debate has focused on the politics of representation and narrative function of working-class spaces, there has been little discussion of this wider sense of place in relation to post-war urban redevelopment. This paper then offers a re-examination of 1960s British cinema through the lens of post-war redevelopment, particularly the huge upheaval related to the “slum clearances” programme enacted between 1955 and 1975 – a process that demolished 1.48 million homes and displaced 3.66 million people in largely working-class areas (Yelling, 2000).

The paper will utilise the social realist films of the British New Wave (1969-1963) as a starting point to plot this relationship – particularly focusing on the often insular and suspicious perspective with which these new spaces are framed, one that reflects the “us versus them” mentality centrally articulated in Hoggart’s influential The Uses of Literacy (1957). However, this paper will also argue that only through examining subsequent and parallel cinematic depictions of working-class urban redevelopment does the cycle’s wider significance in a spatial sense becomes apparent.

The paper will then examine its London-set peers, such as A Place to Go (1963) and Sparrows Can’t Sing (1963), subsequent Northern realism in films like The Whisperers (1967) and Charlie Bubbles (1967), as well as emergent New Towns in I Start Counting (1969) and The Offence (1973). In doing-so this paper will chart the cultural manifestation of post-war redevelopment over the decade, arguing that a key tension emerges within working-class communities between the pull of nostalgia and the optimism promised by such bold, modern and new architectural spaces – debates that still resonate today.

Dr Jonny Smith is currently a researcher and teaching assistant at the University of Manchester, where in April 2022 he completed his AHRC funded PhD titled ‘Nasty, Brutish & Tall: The Utilisation & Representation of Brutalist Architecture in British Cinema Post 1970’. Building on this research, his latest article, ‘Something like the truth’: Confronting the Honesty of Brutalism and Post-War Planning in The Offence, has recently been published in the Journal of British Film and Television.

Christa Kamleithner, Social Mobility Hurts: Berlin’s Märkisches Viertel in Film and Sociology, c. 1970

Film still: Hans and Nina Stürm, Zur Wohnungsfrage, CH 1972.

Abstract

The Märkisches Viertel in West Berlin, built from 1963 onwards, was the most prominent negative example of social housing in German mass media. A commuter estate without a subway connection (which was planned but never realised); today offering a range of social and commercial facilities which were initially lacking; with flats promising a high standard of living but too expensive for many residents at the time. All this led to discontent fuelled by pedagogues, architecture students, filmmakers and numerous leftist activists, including members of the nascent RAF, which manifested itself in demonstrations, magazines, films and television features.

Drawing on rich material from the 1970s and the growing body of secondary literature, the paper focuses on which social class the housing project was intended for, what kind of social transformation was associated with it, and how this was experienced by the actual residents. It discusses films such as Die Wohnungsfrage (1972), made by Hans and Nina Stürm, and Der gekaufte Traum (1977) by Helga Reidemeister, which engage with proletarian families confronted with high rents and new consumer goods that are almost unaffordable for them.

Using promotional films of the project and texts by the sociologist Elisabeth Pfeil, the paper will show that these individuals were struggling with a vision imposed on them: that of double-income families with only one or two children, in possession of a car and a social network extending into the city. Pfeil, arguably West Germany’s most important urban sociologist, had earlier been involved in studies that had led to a disillusionment with the concept of the neighbourhood unit and had created a new social model that described social space as made up of individualised networks. By the 1970s, Pfeil had turned this empirical research into a normative model, which was opposed by the 1968 generation, who revived the concept of community.

Christa Kamleithner is an architectural theorist and cultural historian, whose research focuses on the epistemological and cultural history of built spaces. After holding various academic positions in Austria and Germany, she is currently a postdoc researcher at the University of Konstanz. Together with Susanne Hauser and Roland Meyer, she edited the anthology Architekturwissen (2011/2013), which assembles fundamental texts on the cultural history and theory of built space. In her PhD dissertation Ströme und Zonen, published in 2020 in the Bauwelt Fundamente series, she reconstructs the genealogy of the “functional city” as a media-based process of abstraction. Her current project is dedicated to the history of the “user.”

John van Aitken, Framing Creative Destruction: Shirley Baker, Slum Clearance and the Humanist Imaginary

Hodge Lane Clearances (2014) John van Aitken & Jane Brake.

Abstract

This paper explores the visual culture of creative destruction through Shirley Baker’s photographs of 1960s Salford. The city of Salford continues to be a site of perpetual creative destruction and reimagining. Current scholarship in Baker’s documentary work on post-war Salford is increasingly located in the national imagination, as a definitive image of the losses incurred through slum clearance. In a period where former slum clearance projects are themselves being subject to demolition a re-examination of our understanding of this period seems timely.

The paper considers the iconicity of Baker’s imagery and how its humanist underpinnings have both popularised and obscured the intentions of the work. Baker’s depictions of working-class life in Salford, in a mode sometimes termed the ‘urban pastoral,’ open up a renewed consideration of the cost of table rasa as a form of urban renewal.

Drawing on the authors own first-hand accounts and correspondences with Baker between 2011-2012 it will explore the extent to which her approach humanises the often-abstract process of urban regeneration, a trait that leaves it susceptible to readings of sentimentality and nostalgia. In an era, suspicious of both the ‘poverty safari’ and ‘poverty porn’, the paper will question why this body of work has escaped such criticism. Situating Baker’s work alongside other documentary depictions of Northern working-class life of this period, the paper will question the works newfound popularity and the merit of its humanist method.

John van Aitken is a photographer, researcher and academic. He has been documenting the changes to Salford’s landscape since 2004. Working with writer Jane Brake they have been critically witnessing the slow violence and financialization of Salford’s landscape through the City Council’s policy of property-led redevelopment. Aitken has been a long-term resident of Salford’s Ellor Street Estate. He is a Principal Lecturer at the University of Central Lancashire and a Doctoral Researcher with CREAM at the University of Westminster.

Session Four: EXPERIENCES

Eve Pennington, ‘I’ve Become Somebody who Lives in a Place like This’: Working-class Women’s Construction of Home, Identity, and Memory in Runcorn New Town, c.1970-1989

Housing at the Brow in Runcorn in the late 60s or early 70s. Photo: JR James Archive on Flickr https://flic.kr/p/f7h92z

Abstract

This paper uses Runcorn new town as a case study to explore the relationship between state-led urban redevelopment and working-class women’s construction of ‘home’ in 1970s and 1980s Britain. Much existing historical scholarship on British new towns either focuses on the London overspill towns or privileges the perspectives of male policymakers and planners, neglecting regional perspectives and obscuring residents’ lived experiences. Instead, this paper uses oral history to foreground the gendered, classed, and racialised dimensions of making ‘home’ in a north-west new town. Runcorn was designated as a new town in 1964 to relieve urban overcrowding in nearby North Merseyside. Central government tasked Runcorn Development Corporation with planning and building housing, employment, and infrastructure for 40,000 newcomers. Using Runcorn Development Corporation’s promotional photographs and brochures, the paper suggests that planners designed new housing for white, affluent working-class, nuclear families with breadwinner fathers and homemaker mothers.

To contradict this official perspective, the paper draws on an original oral history interview with a Black working-class woman who moved to Runcorn from London in the 1970s. It explains how her constructions of ‘home’ were mediated by her shifting experiences of poverty and affluence, race and place, family and friendships, and age and life cycle. Her new ‘home’ was a space of economic hardship, restrictive gender roles, and social isolation. Yet it was simultaneously a site of relative affluence, emotional fulfilment, and newfound self-esteem. The paper complicates historical understandings of ‘home’ in twentieth-century Britain by foregrounding the memories of a woman who contradicted the planners’ exclusionary prescriptions about domesticity. The life history methodology forces us to attend to the dynamism and diversity of working-class women’s domestic identities, suggesting that oral history is one of the only ways to understand working-class experiences of urban redevelopment, public housing, and ‘home’.

Eve Pennington is in her second year of a History PhD at the University of Manchester. Her ESRC-funded research project is provisionally titled ‘Mothers of Modernity: Women’s Experiences of New Towns in North-West England, 1961-1989’. It draws on original oral history interviews with women who lived in Skelmersdale, Runcorn, and Central Lancashire New Town during the late twentieth century, and explores their experiences of new housing, communities, employment, and transport. It asks what meanings they attached to their built environment, how they constructed selfhoods in relation or opposition to their towns, and whether the new towns were sites of constraint or opportunity.

Lawrence Cassidy, Signs of The Times. Using material Culture to reclaim a sense of place in District Six and Salford 7

Photo: Lawrence Cassidy

Abstract

In Salford, urban communities have undergone successive waves of housing clearance, contributing to a loss of collective identity and to long term social and spatial segregation. As a creative practitioner, I produce exhibitions utilising items of material culture from destroyed districts in Salford.

The project I currently work on is titled ‘Streets Museum’and is inspired by practice-led PhD research at The District Six Museum, Cape Town, South Africa (2006). I then produced a comparable community-led project in Salford, using related strategies. It is part of a wider debate concerning the eradication of place and the search for appropriate sites of memory to commemorate dispersed populations of post-traumatic landscapes over the past thirty years.

The exhibitions I make rejuvenate a sense of place, facilitating the voices of ex-residents, despite the eradication of the built and social environment. They enable fragmented communities to become active participants in conceptually re-mapping their former localities, facilitating spaces for social networking, regrouping and cultural empowerment.

I collect and exhibit archives of family photographs, home movies, street signs and maps, portraying the community prior to demolition. These archives are designed to personalise the story of housing clearance at local level, as at The District Six Museum, where similar objects are utilised to personalise the story of apartheid. The archives contrast with mass media imagery and documentary photography, which can perpetuate stereotypes of the urban working class as passive victims of a ‘slum’ district, or failed modernist experiment, as in the case of The District Six.

The two urban areas I will explore in terms of spatial analysis and visual representation are firstly, the District Six area of Cape Town, South Africa, which was demolished under apartheid law, including slum clearance acts, and also the Salford 7 district.

Lawrence Cassidy was born in Salford in the 1960s. His family were part of the community clearances of the 1970s. He is currently based in Salford. However, he has also lived and worked in Belfast, Northern Ireland and Mexico, where he was involved in a range of socially engaged art projects. Inspired by his PhD research at Manchester Metropolitan University (2009) on The District Six Museum, Cape Town, South Africa, he founded the ‘Streets Museum’ project. It consists of a series of interactive exhibitions, placed in museums and urban spaces, using material artefacts collected from demolished sites to reconnect displaced urban communities.

Aaron Smith, ‘Sky Children Come Down to Earth’: The Rise and Fall of the Lower Kersal Estate (1962-1990)

Photo: Aaron Smith, Cover page of MArch thesis.

Abstract

The high-rise residential tower blocks that jut out from the urban fabric of much of the UK’s towns and cities are perhaps one of the most divisive building typologies of British domestic architecture. Prior to the second World War, the majority of the UK’s working-class populace were housed in tight rows of terraced housing, built in the shadows of the mills and factories from which Britain’s industrialised economy sprung forth. However, after the conclusion of the second World War the UK’s housing stock had to be rapidly replenished to rehouse the communities displaced both by the destruction caused by war-time bombing raids, as well as pre-existing slum clearance policies introduced to deal with the substandard conditions many Britons were living in. The answer, it seemed, lay in the high-rise residential tower block typology which aimed to tackle the extreme housing demand of the time and limited land availability.

It can be argued in some respects that the typology met these demands successfully, but at what social cost? This research investigates the social impact of the razing of traditional terrace housing communities and subsequent mass adoption of high-rise social housing in post-war Salford on its predominantly working-class populace, through the case study of the Lower Kersal housing estate and the community that formed within its boundary. Compared to other post-war estates of this scale, there isn’t much academic literature concerning the Lower Kersal estate which was the initial impetus behind this research. The research utilises interviews with ex-residents, ex-residents posts on an online forum dedicated to the estate, and contemporaneous newspapers from Salford during the lifetime of the estate to investigate the quality of the community relations on the estate and to what extent was the step up in living conditions enhanced or mitigated by the social impact of high-density living.

Aaron Smith is an Architectural assistant working at Levitt Bernstein’s Manchester office. He graduated from the Manchester School of Architecture (BaHons 2013-2016, MArch 2020-2022) with his student work focusing on sustainable methods of construction, sustainable communities and social housing. His research on the Lower Kersal housing estate in Salford won the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire Dissertation Prize during my Masters. His work and research are very much informed by my own background in a working-class community in Salford and I am particularly interested in Salford’s history of labour movements and social housing.

Session Five: IDEOLOGIES

Sebastian Bietenhader, Matthias Moroder, Emancipatory Architecture of Viennese Public Housing. The Built Re-evaluation of Red Vienna in the First Decade after the Second World War

Eiselsberg-Hof, Vienna, Photo: Thomas Ledl, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4_0 International.

Abstract

Vienna’s late 1940s and 1950s social housing architecture can be considered as modern. However, there are two historical Viennese specificities that complicate this matter. Firstly, the so-called Viennese Modernism of the 1910s and 1920s vehemently rejected some of the core tenets of “International Style”-modernism, by accepting continuities with the history of architecture and the historical urban fabric. Secondly, there is no stark, “modern”, contrast coming from large scale housing in itself, as the interwar period saw the large Red Vienna housing schemes being realized throughout the city.

Focused on rapidly rebuilding after World War II. the architecture in question is often

discussed as being overly rational, and thereby somewhat dull. However, some of this architecture features mostly overlooked formal references to the architecture of Red Vienna, from 1919 to 1934.

In our presentation we will compare a few Viennese housing complexes, the so called “Höfe”, of the post-war-era and the Red-Vienna era respectively. The criteria for comparison are formal articulations of the Höfe, that are clearly referential or even hint at a similar typology as schemes from both eras that share the same planners – which was not uncommon, as they were excluded from work in the fascist era and then returned.With this comparison, we want to precisely re-trace the post-war architecture. We propose to interpret it as a re-evaluation in built-form of the Austro-Marxist emancipatory architecture. Our presentation illustrates one of the architectural elements that will be discussed: Housing that bridges over streets – a classic Red Vienna trait that emphasizes public ownership beyond the perimeter, is taken up by many post-war Höfe, however its employment is less ostentatious.

Through this comparison we hope to highlight the specific formal qualities of Red Vienna emancipatory architecture, specifically through reading them against the more neutral rendition of the post-war-era.

Sebastian Bietenhader and Matthias Moroder have been working together as Büro Bietenhader Moroder since 2015. Büro Bietenhader Moroder deals with copyness as a positive formal property of architecture, which makes it possible to work formally against the neoliberal architecture of differentiation, flexibility and individualization. By simultaneously maximizing the formal relations of architectural settings to one another, which is conceptually defined as copyness, Büro Bietenhader Moroder opens up a re-reading of the formal characteristics of social housing of French and Russian revolutionary architecture and that of Red Vienna. Büro Bietenhader Moroder formulates a way out of the purely expedient handling of planning tools by placing the structure of methods and a materialistic analysis of the software at the centre of the design.

Sebastian Bietenhader currently lives in Zurich with his partner and his child. He studied architecture at the ETH Zurich (BSc.) and at the Harvard GSD, as well as history and philosophy of knowledge, also at the ETH Zurich (MSc.), where he did a thesis on the development of the computer modelling space, which will be essential for BIM. He headed the student discussion group “Ambitus”, in which the upcoming wave of emeritus professions from 2014 onwards was prepared and accompanied in terms of university policy in the ETH Department of Architecture. He is a regular guest critic at the ETH and has been teaching architecture at EASA, the Vienna Architecture Summer School and the Technical University Vienna.

Matthias Moroder studied architecture (AA Dipl.) at the Architectural Association in London, art history (BA) and philosophy (BA) at the University of Vienna and history and theory of architecture (MAS) at the ETH Zurich. In 2018 he co-founded MAGAZIN, an independent exhibition space for architecture in Vienna, which he is co-leading with Jerome Becker. He is currently a PhD student at the department of art history of the University of Vienna doing a thesis on the architectural theory and architecture of Viennese architect Hermann Czech. Matthias thought architecture history and theory at the University of Vienna as well as architecture at AA Summer Schools in South Korea, EASA 2021/2022, the Vienna Architecture Summer School 2022 and at the Technical University Vienna. He has been an invited critic at the AA, TU Vienna, University of Innsbruck, Politecnico di Milano, University of Toronto, the University of Southern California and at KU Leuven.

Violeta Stefanović, The collective housing complexes of socialist Yugoslavia – a new form of housing for a new society and its communities

A neighbourhood event, Liman IV, Novi Sad, Serbia; 4th of June, 2022. Photo: Violeta Stefanović.

Abstract

The rapid industrialisation and accompanying housing crisis that occurred soon after the formation of socialist Yugoslavia after the Second World War became two preconditions for the envisioning of residential architecture, one of the focal points of the state’s apparatus. In this ambitious venture, architects were guided by two ideologies: socialist and modernist. Their correlation is embodied in the spatial solutions of collective housing complexes, making them the complex result of the symbiosis of a strong architectural idea and the driven state apparatus.

The separation from former concepts of urban planning served as a means for the formation of new massive housing complexes, which were to be widespread throughout all of the Federation’s republics. With the introduction of a new architectural expression encompassing important and manifold meanings, it became a hallmark of the newly-formed state, connecting the republics, strengthening and highlighting their unity. Housing represents the existential spatial frame for the everyday lives of its residents, highly impacting the manner in which their day-to-day existence is realised.

The citizens of the new state suddenly underwent a profound change in their everyday lives, stemming from the extremely different living environment they were now inhabiting. The migration of citizens, from rural to urban environments, from privately owned traditionally built single-family dwellings to state (publicly) owned collective housing complexes, drastically changed the living conditions and the circumstances for the creation of interpersonal relations between residents.

Relying on social theories referring to communities and the relation between space and identity, the aim of this paper is to research the ways in which massive collective housing complexes of socialist Yugoslavia changed city life in accordance with the social-political characteristics of the new state and society, influencing the way in which the residents of collective housing complexes form social relations, communal values and communities as a whole.

Violeta Stefanović (1994), M.Sc. Arch. and PhD candidate is a Senior Scientific Researcher at the University of Novi Sad, Faculty of Technical Sciences, Department of Architecture and Urbanism in Novi Sad, Serbia. The focus of her research is the modernist architecture of socialist Yugoslavia, particularly collective housing complexes and their resulting communities. Her work has been published in a number of monographies and she has internationally presented and published many scientific papers pertaining to the topics of her main research field. She has also curated two international architectural exhibitions and was the editor of three exhibition catalogues.

Julian Beqiri, Tirana in between communism and a turbulent encounter to modernisation: The Palace of Culture replacing the Old Bazaar.

The Palace of Culture and the Skanderbeg Square: A forced cohabitation. Tirana. Collage: Julian Beqiri, 2016.

Abstract

The post WWII European context of urban reconstruction is extensively studied but the development policies of non-EU capital cities remain largely unexplored.

This article investigates the urban reconstruction strategy that shaped the centre of Tirana during the early years of the communist regime when the Palace of Culture was also built. Completed in 1966 with President Nikita Khrushchev symbolically laying the first brick, it became part of a large and radical modernisation program which echoed the Soviet aesthetics of socialist realism. The new structure replaced the old bazaar which dated back in the beginning of the 16th century when the city of Tirana began to develop. The clearance of the old bazaar was one of the first imperative measures towards creating the socialist city and an attempt to complete the detachment from the Ottoman legacy. This study sheds light on a specific demolition-based urban reconstruction strategy which used to characterize Albanian communism as a strong central governmental authority over local planning.

As the formal centre of a typical feudalistic town, the bazaar posed a viable antithesis of the centralized economy – one of the pillars of communism. Together with removing the country from Ottoman influences the adopted strategy was part of the efforts which likewise intended to overturn the local status quo.

However, rather than underlying the points of friction between communism and the city’s Ottoman legacy, the main objective of this research is to reveal the multifaceted character of the post-war reconstruction policies which aimed at transforming the city to a concrete spatial agenda for Marxism.

Julian Beqiri is an architect, urbanist and researcher. He holds a master’s degree in Architecture from Polytechnic University of Tirana, Albania and a master’s degree in Urbanism from Delft University of Technology, Netherlands. From 2016 to 2020 Julian worked as an architect at OMA (Office for Metropolitan Architecture) in Rotterdam, and in November 2020 joined the academic staff of EPOKA University, Tirana. Apart from teaching and writing Julian leads the design practice DISPACED (Dialectics of Space Design) based in Tirana, Albania.

Eleni, Axioti, The formation of a new class ideology: the role of higher education and culture architecture in the transformation of the British working class in the post-war welfare state.

Hayward Gallery, London. Photo : Eleni Axioti, 2009.

Abstract

This paper discusses the role of higher education and cultural buildings of the British welfare state and how their architecture relates to the formation of a new class ideology for the working class. Initially, the paper discusses the ideal of education and culture for all, which was intended to improve the lives of people independently of their socio- economic status. The paper investigates how the university and cultural building programs of the post-war British welfare state aimed to educate the population and shape them as modern social citizens. While the expansion of higher education in the 1960s facilitated the transition of the workforce from blue to white-collar workers. .

The paper will then address the gradual transformation of these spaces by the promotion of commercialization and entrepreneurship, especially through the increased importance of consumption and leisure since the 1960s. It will examine how these practices implemented an ideology of individualism within spaces that were built for the working class, which eventually achieved the depoliticization of these spaces. The paper concludes by reflecting on the contemporary privatized learning and cultural spaces and the role of architecture in the creation of factories of commercialized knowledge.

Eleni Axioti is a researcher, and an educator. She is lecturer in contextual studies at the University of the Arts London and course tutor in history and theory studies at the Architectural Association School of Architecture, teaching at Diploma school and leading the second year of HTS studies. She holds a Ph.D. and an MA in Histories and Theories of Architecture from the Architectural Association. She has practiced as a designer and researcher in London since 2008. Her research focuses on architectural history in regard to issues of social policy and political economy.

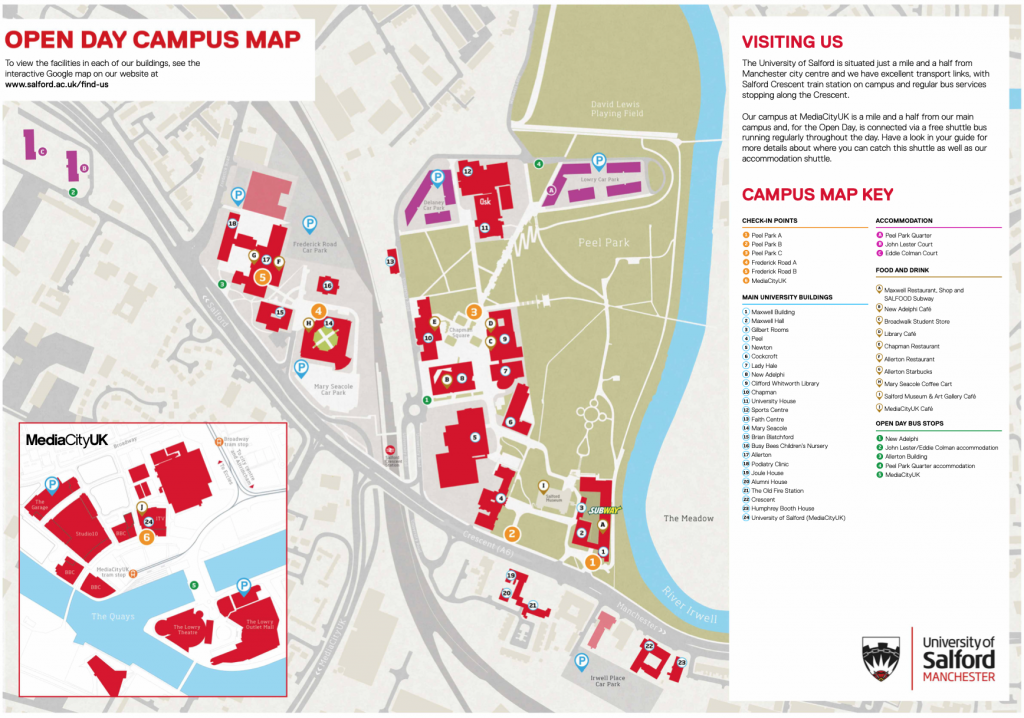

Campus Map – University of Salford

Traveling to Campus

Travelling to the University of Salford and venue:

Travelling to the University of Salford:

Travel | University of Salford

Hotels

The two hotels we recommend are:

The Holiday Inn MediaCityUK, at the special negotiated rate of £102 per night. This includes breakfast and Wifi,

Please contact the hotel directly on +44 (0)161 813 1040, or email reservations on reservations@himediacityuk.co.uk, and quote “University of Salford”.

OR

The Ainscow Hotel, at the special negotiated rate of £79 per night. This includes breakfast and Wifi.

Please contact the hotel directly on +44 (0)161 827 1650 , or email reservations on enquiries@theainscow.com and quote “University of Salford”.