by Bill Longshaw

I was lucky enough to meet Coronation Street creator Tony Warren when he opened my exhibition, ‘1962’ at the Lowry in 2002. He was notoriously reluctant to talk about the street, so most of the information here comes from PhD research, conducted around the same time. During these studies, I also met set designer Dennis Parkin, who was far more willing to talk about his part in the creation of the street’s early set, or sets…

Just over a year ago, Granada Television unveiled the latest addition to its Coronation Street set. ‘The Precinct’, represented a radical departure for a set that had evolved throughout the street’s 63 years. The mixture of flats and shops, with an adjoining playground, gave a new opportunity to do what ‘the street’ had always done by looking forwards, backwards and sideways at the life of Weatherfield; Tony Warren’s small-screen recreation of his native Salford. The Soap’s characters had long talked about ‘going down the precinct’ and viewers, no doubt, imagined a down-at-heel piece of ‘60s architecture that had presumably faired as badly as many such developments across the northwest. Then, after decades of having to imagine it, like the also never-seen ‘red rec’, suddenly, there it was! Complete with a takeaway, pound shop, charity shop and most notably, bearing in mind the times we live in, a pawnbroker’s shop.

When Coronation Street was first aired in December 1960, it seemed to fit into the emerging genre of social realism, echoing popular ‘kitchen sink’ drama films like Saturday Night and Sunday, which showed working class life in the raw – stark and confrontational and shot in modish black and white. Bored of serialising popular fiction, Granada continuity writer, Tony Warren persuaded his bosses that he too should be writing about what he knew best. Television was a young medium (Warren himself was only 24) and although many of the Granada bosses believed the box in the living room should provide an escape from the drab realities of the North, they were at least willing to push the boundaries a little. A pilot was made, although to be on the safe side, the bosses insisted on showing the episode to anyone and everyone at the Quay Street studios, including secretaries, technicians and canteen staff, to gauge opinion before finally agreeing to broadcast the show; which, until the very last minute was to be named Florizel Street. Warren based his series on the terraced streets of Pendlebury, where he grew up. In some ways it was a slice of innovative social realism, but was it ever real? It had a typical street with a pub at one end and a corner shop at the other -based on Archie Street in Salford – and an ensemble of characters who wrestled with ‘real-life’ problems. However, it was just as much a slice of nostalgia; an elegy for a world that by 1960 was already disappearing fast. Indeed, as if to emphasise the ephemeral nature of the subject matter, Granada, still worried that the show might flop, initially only commissioned 13 episodes and suggested that if it was not well-received, then the series might be brought crashing down by a decision to demolish the street as part of some imagined Weatherfield slum-clearance programme. Of course, we know today that the street was an almost instant success, but it is still interesting to wonder what would have happened if the greater truth of demolition and subsequent scattering of Warren’s lovingly assembled community had been allowed to happen. The way the North, as a whole, and Salford in particular were and are perceived by the Nation would certainly have been totally different…

Thanks to Coronation Street, many of us have grown up with a nuanced, nostalgic vision of the North implanted in our brains. A reconstructed version of itself, that Warren and the writers who came after him lovingly put together and nurtured, like some kind of living museum exhibit. Yes, it had the real story lines of poverty and hardship. Storylines that have evolved, over decades, to include murder, drugs and all the other nastiness 21st century continuing dramas demand, reflected in things like the precinct’s pawnbrokers. but Coronation Street’s North also had warmth, wit and sentimentality at its core. A warmth of a mythical past, infused with the kind of porky, northern humour that was the bread and butter of Warren’s original cast. Many of whom were veterans of BBC regional radio, music hall and rep theatre. Coronation Street initially represented an attempt to show Salford as something real and yet not real. Partly itself, but also partly how we would like to think of it; broadcasting instant nostalgia for a world of ‘tight-knit’ streets that never really existed. Today the truth of this world remains elusive like all social realism. Shrouded in sentimentally and in recent years increasingly obscured too by a growing need to create evermore sensational and at times disturbing storylines.

The original set was designed by Dennis Parkin, who began work as a shop fitter and thus found his talent for quick-turnaround joinery much in demand in the new medium of television. His original design came in two parts, as the sound stage at Granada was not large enough to accommodate the whole street from end to end. This meant that no episode could include both the outside of the shop and the pub. Indeed, for a time, scriptwriters had to tailor their storylines accordingly. It was only when the continuing drama was bedded in and set to run and run that a more permanent set was constructed on the back lot of the Quay Street Studios. This was later rebuilt in the 1970s for colour television and has subsequently been rebuilt on several occasions. Most notably when the whole production moved to its new, permanent, site next to the Imperial War Museum North in 2012. A relocation which also allowed Granada to create a much-enlarged set, fit for 21st Century High-Definition Television.

Warren’s Weatherfield remains the most well-known and loved version of Salford seen on screen. Although, remarkably, in just 20 years between 1940 and the birth of the street in 1960 there were several other, attempts to build, or rebuild the classic working-class terraces of Salford. In 1941, the film of Walter Greenwood’s novel, Love on the Dole included a fairly generic terraced street set. Built at Rock studios, Borehamwood, Herts it included a pawnbroker’s that was integral to the storyline. The wartime film portrayed the sheer misery of life in Salford’s Hanky Park and bearing in mind the winds of change beginning to blow through Britain, set out, from its patriotic opening titles to act as a warning and a rallying cry for the builders of a better Britain.[i] Portraying the kind of the world that we surely would never have to go back to. After the war, in 1954, Director David Lean’s film of the play Hobson’s Choice, centred on another recreated Salford Street; this time, built at Shepperton Studios. Interestingly, Lean nevertheless insisted on coming North to film some scenes on location. Notably in Peel Park and amongst nearby streets many of which were already earmarked for demolition. It was almost as if Lean too was trying to show that while we were welcome to feel some nostalgia, we should never let the down-at-heel, essentially Victorian world he found in parts of Salford come back.[ii]

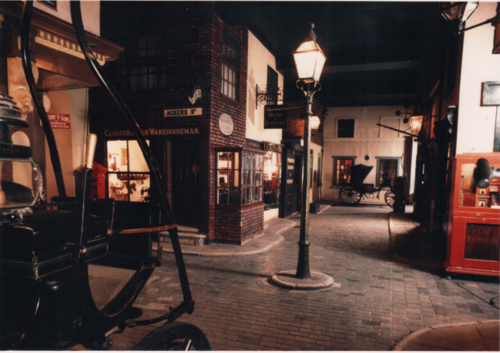

Christmas concert, Salford Choral Society and Friends of Salford Museums Association, in Lark Hill Place. Printed in the Salford City Reporter 16th Dec 1966, Digital Salford: DM00093.

In the late 1950s, these themes were echoed when Salford Museum Curator Ted Frape began work on Lark Hill Place, and recreated a Victorian street within the Salford Museum and Art Gallery. Here, once again, is that mixture of nostalgia and a feeling that the reconstruction should act as a line in the sand. A warning that we should be leaving the dark days of Victoria, with the hardships of poor housing, child labour, disease and the weekly trips to the pawnbrokers for good. This, of course, brings us to Tony Waren and his street. Realised in wood, plaster and faux-brick by Denis Parkin and based on real-life Archie Steet in Salford. As we have seen, it gave a new level of social realism in some senses, but not in others. It provided a view of the North that was gritty, but also acknowledged the power of nostalgia and the real need of community, humour and common sense to pull us through hard times. It is interesting to wonder what the ‘re-makers’ of Salford – from the team which filmed Love on the Dole, to those who built Lark Hill Place – would think about a ‘brand new’ pawnbrokers appearing on the street in the second decade of the 21st Century.

[i] There were plans to produce a film version of Love on the Dole in the late 1930s, but the British Board of Film Classification refused to grant a certificate as they considered the subject matter too sordid and likely to stir up unrest, particularly in the north. During wartime the production was sanctioned and it became a propaganda piece with opening titles rallying the nation and proclaiming that we should never go back to such dark days.

[ii] Lean’s location filming included scenes of Peel Park, where the Salford Fire Brigade famously had to spray foam onto the river Irwell to make it look more polluted. He also filmed in streets around Salford Town Hall, including Church Street and East Market Street.