Sarah Hardacre, a practicing artist with strong connections to Salford has written our guest post for this week. She has kindly allowed us to feature example of her work which is a real treat. Enjoy!

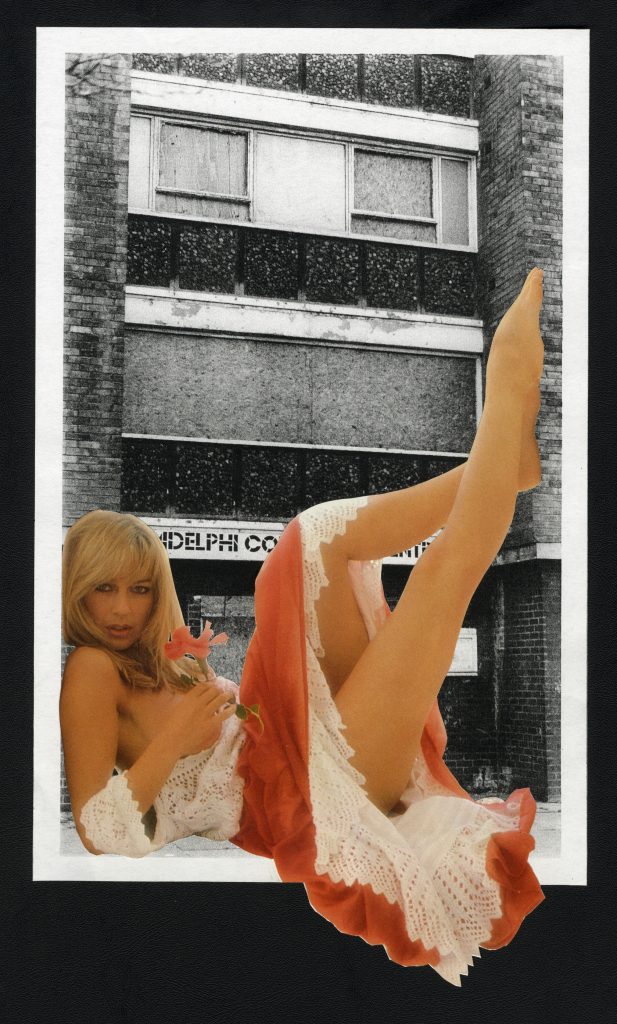

Salford is where I made my home in the late 1990s, when I moved from the rural hills of the West Yorkshire Pennines to the urban heights of Adelphi Court; a fourteen-storey tower block in the Trinity Riverside area of Salford. I was wowed by the parties, the bright lights of the city, the nightlife and a way of living that was just so exciting to a young country girl. The contrast was mesmerizing; from the stone-built terraces of Victorian era mill towns to a municipal Modernist inspired block of flats. I can only imagine then, about the experiences of the communities in this very area, who were moved from their back-to-back houses and into the brand new buildings that resulted from the nationwide programmes of residential urban renewal from the 1950s to 1970s.

My flat was on the 14th floor and the view was out over Pendleton, taking in those stunning Blade Runner sunsets that crown the ‘Salford Shopping City’ and what was the Ellor Street Redevelopment area of the 1960s; a scheme that replaced Hankinson Park, known locally as ‘Hanky Park’, a large post-industrial, working-class area of terraced dwellings deemed unfit by the Council and slated for demolition in the 1930s.

From the moment I moved into Adelphi Court, my love affair with Salford, with Modernist Architecture and the history of urban redevelopment and the social histories of the working-class communities it changed was completely cemented.

Connections to this area ran deep. My Grandma, Renée Blackburn, used to tell me stories of visiting the TGWU Building that sat at the corner of The Crescent and Oldfield Road. She was a shop floor union representative in the mills of the Rossendale Valley and would travel to Salford for union AGMs and regional meetings. Opened in 1937 by Ernest Bevan, Head of the TGWU, Transport House was flattened in 2007, despite being within the Crescent Conservation area and on a local list of buildings of architectural interest. Renée was my hero. And living in this area of Salford, I felt like I was somehow walking in her footsteps and building a bridge to my family’s own working class history. The stories of Marx and Engels who met in The Crescent Pub to discuss writing the Communist Manifesto just added an extra element excitement to the histories that lay at my feet here.

In 2005 I left my job with the NHS, working with the Manchester Drug Service and embarked on a journey of creative discovery, enrolling on the Visual Arts BA(Hons) course at the University of Salford. It was here that I found the Salford Local History Library, located in the Salford Museum & Art Gallery on the main Peel Park campus along The Crescent. The history of this library is itself significant. Opened in 1850 as ‘The Royal Museum & Public Library’ it was the first unconditionally free public library in England. Before this, libraries were run by paid subscription and were the domain of the richer upper classes. Campaigners for free libraries felt that encouraging the lower classes to engage in ‘morally uplifting’ activities such as reading would ‘promote greater social good’ (1). And so followed the Public Libraries Act of 1850 which was the first legislative step in establishing a national institution of universal free access to information and literature.

Aside from its unique history, the Salford Local History Library held a cavern of treasure in its photographic archive, and I became obsessed with sifting through the abundance of images and started spending most of my free time there, wearing a groove in the carpet between the reference card cupboards and the filing cabinets that held my holy grail of architectural documentation. What I loved so much about this library and this image archive, aside from it being a discovery of my local area and its history, was that the process of searching was physical; the photographs were there in front of you to touch and the opportunity for unexpected discoveries were right at your finger tips.

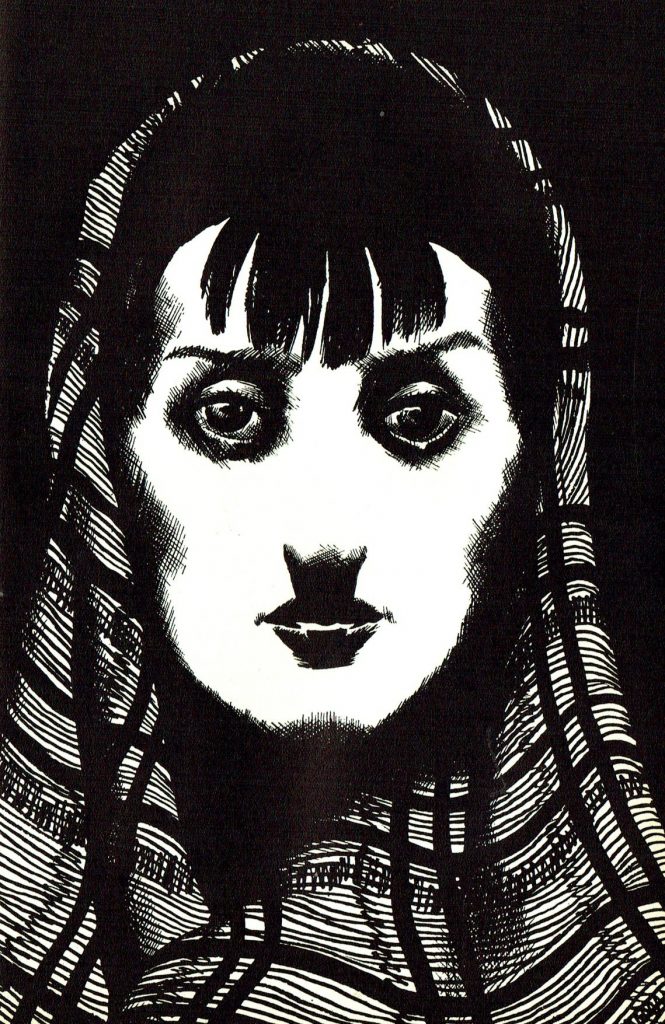

So it was an unexpected surprise when through this archive I came across Walter Greenwood and his writing, which became a significant influence to my emerging collage practice towards the end of my degree study in 2008. First it was the novel ‘Love on the Dole’, which told the story of the people of ‘Hanky Park’ where Greenwood was born, who were pushed into poverty by the Great Depression (1929-39). Digging deeper into Greenwood’s work, I came across a first edition copy of ‘The Cleft Stick’, a series of short stories written mostly before ‘Love on the Dole’ it included many of the same characters. Wonderfully illustrated with dramatic drawings by artist Arthur Wragg from Eccles, the book visually brought to life the conditions of Hanky Park and its inhabitants. Before I knew it I had a small collection of Greenwood works in my studio. But it was when I bought a copy of the published script for ‘The Cure For Love: A Lancashire Comedy’ and opened the first page to “ACT 1: MRS. SARAH HARDACRE’S Kitchen-living-room” that I was totally hooked; personally connected, invested and finding a complete sense of myself in these works and this very particular area of Salford.

Throughout Greenwood’s works, it was always the stories of the women that resonated with me most. In ‘Love on the Dole’, I empathized with Sally Hardcastle, who lost the love of her life, Larry Meath, a socialist agitator, when he was struck on the head by a Policeman’s truncheon. Feeling inferior to Larry’s socialist intellectualism, she gives in to the affections of a local bookmaker who provides work for both her father and brother, herself becoming the victim of economic and idealistic poverty. And Mrs Hardcastle, the matriarch of the family whom Greenwood never does afford a given name, keeping the family together by pawning their Sunday Best each week, just to scrape together the money to get it out of the shop again for church. Not just a housewife, Mrs Hardcastle and the other women of North Street kept that community together; looking after the kids, nursing the sick, financially supporting neighbours who fell on hard times, taking in waifs and strays. It was always the characters of these strong women, like my grandma, who just kept on going and did everything they could to survive, that set the fire in my belly and made me want to tell a woman’s story.

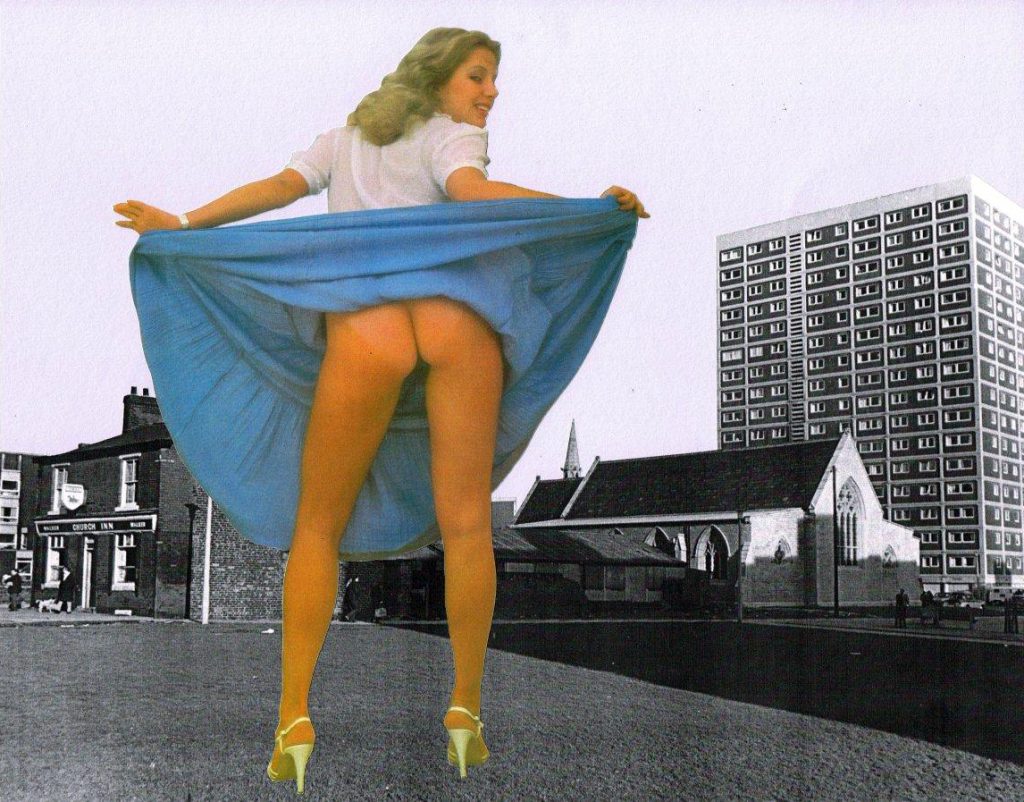

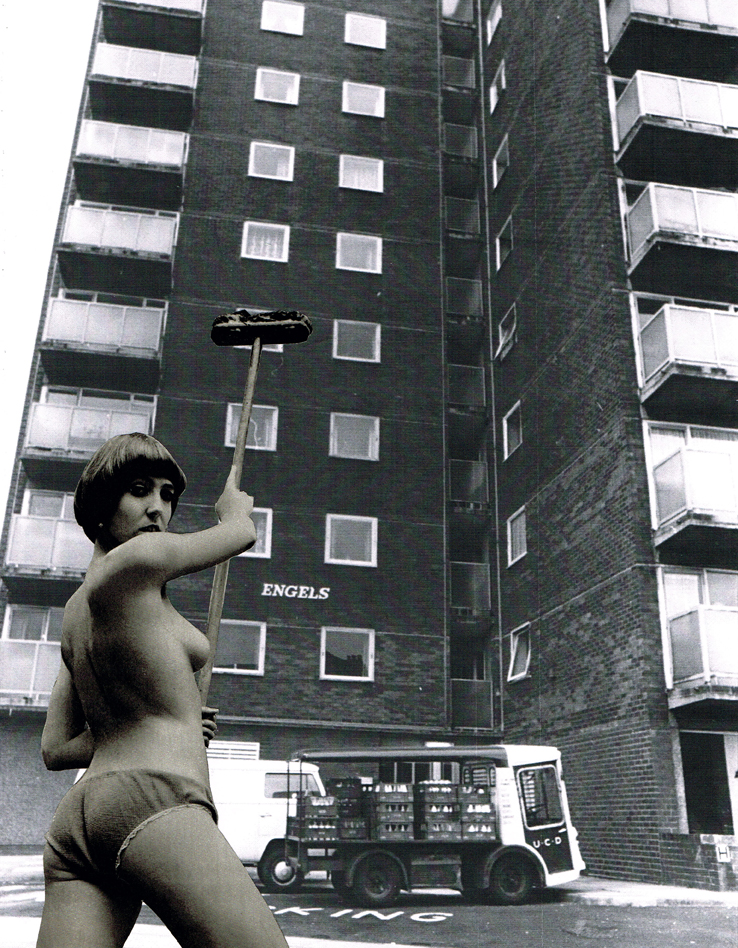

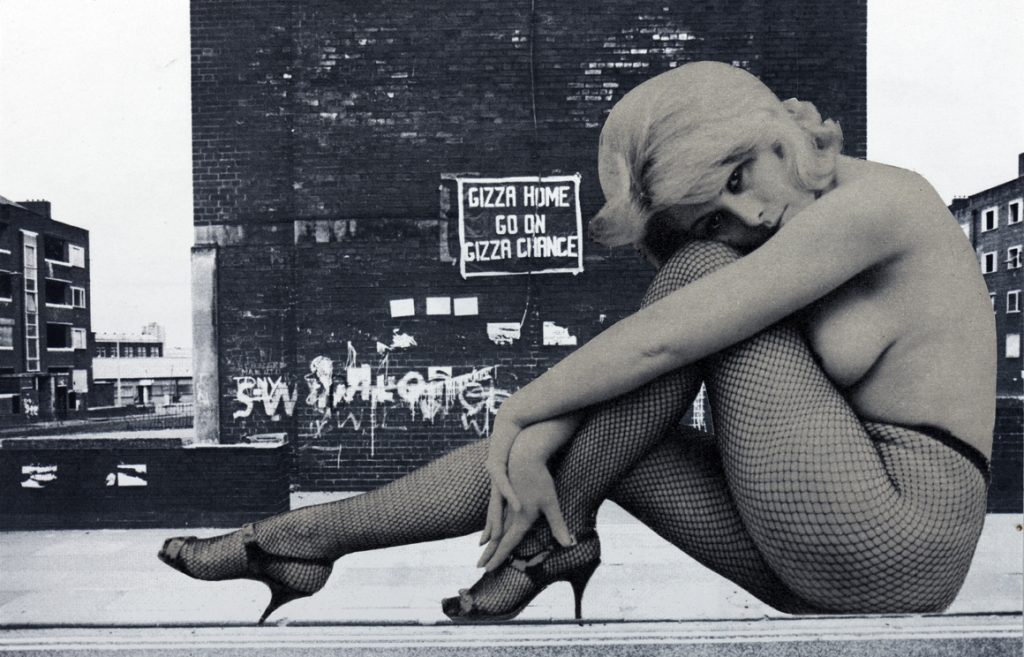

From my Grandma in the TGWU, to my 14th floor apartment, into the archives of the Salford Local History Library and out through the eyes of Greenwood’s matriarchs, I began to weave Salford into my artwork. I had a rich source of imagery in the archives and my focus was set on the Ellor Street redevelopment area of Pendleton. Why and when exactly I took up a vintage ‘Gentlemen’s Magazine’ and threw that into the mix of my collages I can’t for the life of me remember. It’s a question I get asked all the time and one I just don’t have an answer for other than it must’ve been something so unconscious, sheer happenstance, a mere serendipitous flash! But when it happened it just worked and became my visual language for what I wanted to say.

Taking these women away from the male gaze of the magazine page and putting them in a new setting, themselves then looking out, it became as though they were questioning the gaze; “What are you looking at?”. They become towering matriarchs, echoing Nancy’s experiences in the 1958 film ‘Attack of the 50 Foot woman, breaking free from their restraints. Giant goddesses of community protection. Sally Hardcastle perhaps, finally doing what she wants to do and not what’s expected of her.

In other ways, my work is a visible complexion of contradictions and paradox. Grit and glamour. Bare building materials against bare flesh. Structural architectural elements juxtapose naturally curvaceous figures. Richard Brook, Professor of Architecture & Urbanism at the Manchester School of Architecture notes that my practice is “Characterised by a surfeit of internal contradictions. By placing these contemporaneous subjects together in such deceptively simple compositions Sarah Hardacre enables a political view, enshrined in the personal and private.” (3)

It’s in these tensions between the public and the private that I find the most playfulness in my works. Between the public sphere of municipal housing design and urban planning and the role of women within the home. Architecture was very much a male dominated profession, yet the home is the domain of the woman, so another contradiction arises in that “final decision making on housing design, on women’s real needs, desires and aspirations are not taken as seriously as male-dominated ideas about the appropriate house for a family.” (2) Turning the inside out and putting something at once private and intimate firmly into the public realm, wide open for all to see. In this way I’m questioning notions of domestication while also investigating how women interact in the man made world and find their place within the home, as well as the urban built environment. And interrogating the complex relationships between architecture and women’s bodies, the gendered language of buildings and a feminist aesthetics of space.

Beyond the women in my work, I’m also drawn to the contradictory tensions within the architecture of Salford that provides the backdrop in my practice. I’m so enchanted by the utopian visions of municipal planning ideals and the Modernist philosophies of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries that led to the Ellor Street Redevelopment; the conception of the NHS, the formation of the Welfare State, the post-war building of ‘Homes for Heroes’ and the creation of new modern dwellings that brought with them the future and so much promise.

But this was short lived, and it wasn’t long before these structures of hope crumbled, sometimes physically as well as metaphorically and the estates that were built to replace the working-class slums of the industrialised North were themselves at the root of social issues, economic decline and the victims of a lack of investment and maintenance from the councils that built them.

And what next for Salford? While the towering beacon of ‘Salford Shopping City’s Briarfield Court and the main buildings of the Ellor Street Redevelopment area still stand, the grumble of the urban regeneration machine groans on with the Salford Crescent Masterplan and a new £650 million scheme to transform Pendleton already underway, the capitalising cries of the Northern Powerhouse can be heard echoing around the last corners of these areas of managed decline.

References:

1. Simkin, John (September 1997-June 2013) – British History > British Education > 1850 Public Library Act > Public Libraries Act https://web.archive.org/web/20140316170538/http:/www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/Llibrary.htm [22nd October 2022]

2. MATRIX (1985) Making Space: Women And The Man Made Environment. London, Pluto Press. 3. Hardacre, Sarah (2021) In Touch With Tomorrow. Manchester, The Modernist