This week we have another guest post by Dr Deborah Woodman from the University of Salford.

One of the cornerstones of northern working-class life was that of the public house. Centred around a pint a whole culture existed. Community, gossip, finding work, gambling, day trips, friendly societies, the list is endless in the role of pubs serving their localities. Like its neighbour Manchester, and other towns in the region, Salford has had its fair share of boozers in tight-knit working-class communities. Salford was also home to some famous brewing names, such as Threlfalls Chesters and Groves & Whitnall, whose breweries on Cook Street and Regent Road respectively serviced many of the region’s locals. Ironically, the one institution that brought communities together has been one that struggled to survive modernisation when housing stocks were demolished to make way for new developments. Whilst redevelopment was often necessary, the removal of housing and many people’s local pubs broke up strong community ties that had unwanted consequences. Here, we look at the role of compulsory purchase in the pub trade, such as the relationship between brewers and authorities, what happened to pubs in Salford during the slum clearances of the 1960s, and the legacy it left. At the turn of the twentieth century, there were in the region of 150 pubs and 240 beerhouses in Salford.[i] Of these, only a handful have survived different stages of redevelopment since the 1960s.

Pressure on the pub trade was evident right at the start of the twentieth century, in part because of the Temperance Movement, successive Liberal governments which made life difficult for the drink trade, followed by World War One. Many pubs were affected by the Licensing (Compensation) Act of 1904, where the authorities could decide to offer compensation if they chose not to renew a license in a bid to curb pub numbers, and this was already leading to a loss in the number of pubs in Salford, especially around the Chapel Street and Greengate area, where many properties were not only in poor condition but were seemingly attracting a ‘low class’ of drinker that exacerbated drunkenness. Many of the buildings were admittedly in a very poor state and some pubs were selling so little beer it was difficult to justify their survival.

The notion that there were too many pubs resurfaced during the mid-twentieth century as part of plans to modernise areas of Salford, which created tensions between the authorities, brewers and the local community.

A 1950 public enquiry into Salford’s proposed slum clearance scheme interviewed some of those affected. This included 80-year-old George Turton who for 45 years had managed the Stephen’s Tavern. He did not want to move despite Salford’s authorities condemning his premises, since after all, it had been home, business, and a lifetime of memories. There was also Edith Chadderton who ran an off-license in Brewery Street. She had been born there 41 years earlier and argued that there was nothing wrong with the property.[ii] At a 1959 public inquiry, the issue over the state of some pub properties resurfaced. The Red Lion and Miners Arms had been regarded as unfit for habitation, and brewers were accused of sufficiently renovating the properties to obtain a greater level of compensation. This dispute also argued over how much brewers had invested to make these properties viable.[iii]

The number of pubs in the area was raised at the 1954 Licensed Retailers Association’s annual banquet by the Mayor of Salford, Joseph Shlosberg, who suggested that a ballot should be held to decide which ones to keep open. Whilst this comment may have been made in jest, there was consensus that publicans and brewers were finding slum clearance a particular problem where many locals in clearance areas remained standing despite their diminished customer base.[iv] Much of this problem centred around negotiations between the authorities and brewers over the level of compensation. Salford Council was facing a bill of around £280,000 for compensation of 29 public houses. The bill was mounting and even starting to affect wider housing rents to recoup some of the costs.

One local councillor, Alderman Goulden, described how in one demolition area nine pubs were standing ‘like sentinels in the desert’ with little or no custom and hampering wider housing redevelopment.

Often compensation did not reflect the turnover of pubs and council members felt that brewers were given preferential treatment with both the generous valuation of pubs and favourable sites for rebuilds. Shopkeepers, for example, were given compensation based on the previous six months’ trading, so seemingly little in comparison to the generosity brewers were obtaining for dilapidated properties not worth saving.[v] A special council committee was implemented to review payments to brewers since the cost was estimated to be around 30 per cent of the total clearance budget.[vi] Unsurprisingly, brewers were of a different opinion, For example, in 1960 Groves & Whitnall lost three pubs and three off-licenses, with a further anticipated loss of 20 pubs and 11 off-licences, which in their opinion would take considerable time to absorb such shortfalls.[vii] It appeared that two to three pub licenses were lost for the gain of just one, so brewers’ losses were mounting, and pubs selling the most beer were offered first refusal of preferential sites.[viii]

One of the more well-known pubs lost in Salford was the William IV in East Ordsall Lane, owned by Manchester-based brewer, Joseph Holt, which closed in 1960 to make way for the Islington redevelopment, and whose bar formed part of one of the most famous pubs in the country, that of the Rovers Return in the long-running soap, Coronation Street.[ix] The area around Ellor Street was especially impacted by compulsory purchase and on 28 April 1963, coined ‘Black Sunday’, seven out of eight doomed pubs closed their doors the same weekend for the last time, the loss including the Miners Arms, British Queen, and the Oddfellows Arms. They were indeed ‘like sentinels in the desert’ as the only buildings standing after the demolition of the surrounding neighbourhoods.

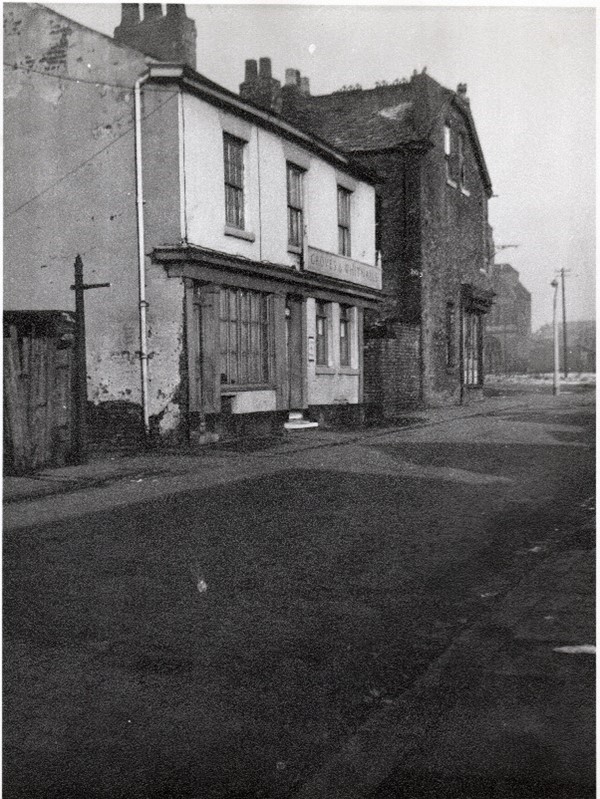

This is captured perfectly with the British Queen public house, here in splendid isolation in an image that depicts the scene better than any written description could. Many of their former customers came from their new neighbourhoods right up until this last weekend, in a sense of loyalty that the tight-knit communities often displayed. The British Queen, which dated back to the 1850s, was acquired by compulsory purchase order in early 1960 as part of the Ellor Street clearance, and served its last pint at the lunchtime session on Black Sunday. The Salford City Reporter newspaper wrote how,

‘the pumps were empty, and the bottle shelves were bare’ and the pubs themselves ‘like islands in a sea of rubble’.[x]

The Miners Arms was another casualty that fateful weekend in 1963. The pub’s last licensee was Elsie Walters, and after 14 years at age 72, the closure must surely have been a wrench, which had been hanging there since a compulsory purchase order was served back in 1959. In an interview with the Salford City Reporter a few days before Black Sunday, Mrs Walters said, ‘I’m lucky if I can fill a table on weekdays, but they’re very loyal on Saturday nights; some of them come a five-penny bus ride to drink here again. But the ladies don’t like coming down from Broad Street, with no streetlights and all the bricks.’[xi]

The Oddfellows Arms had a similar experience. A former beerhouse from the 1840s, by the turn of the twentieth century, it was owned by Groves & Whitnall. The pub had been up for closure previously when in 1908 the authorities decided it was not viable with so few customers and poor conditions. Groves & Whitnall invested in the property and the pub survived until 1965 when it succumbed to the Ellor Street clearance.

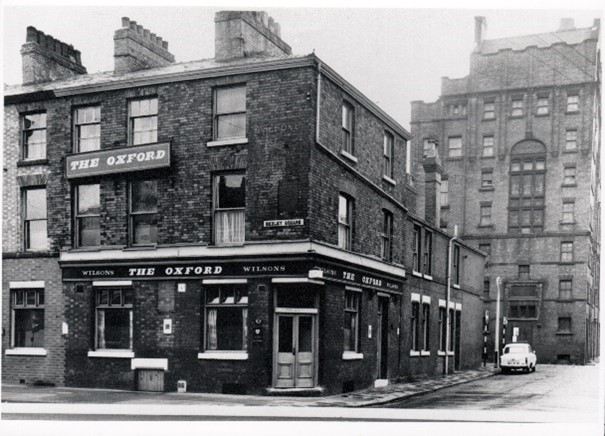

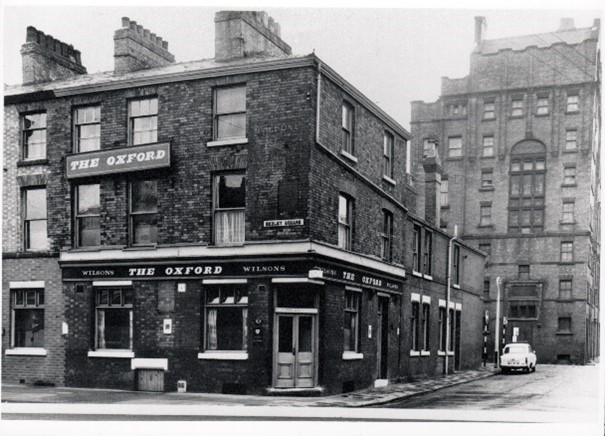

So, was the removal of these pubs worth it and what has survived? Well of the nine or so that were built in the 1970s to replace some of the losses, only the Winston has survived to date, with some only surviving twenty years or so. There is a mere handful that remains with us today that were there before the slum clearance, and most of these are along the Manchester/Salford border in and around Trinity Way and the Chapel Street area. Starting with the Eagle Inn, which can be seen off Trinity Way, is a Grade II listed terracotta-inspired building, the current one dating from 1902 but on a site that has had a pub since the 1840s. During the 1890s the Eagle was owned by the Crumpsall Brewery Company, followed by Joseph Holts Brewery from 1897, who rebuilt the premises that we currently see. Further along Trinity is the Black Friar, another Grade II listed pub dating from the 1880s, formerly owned by Boddingtons Brewery, that was closed for around 15 years following a fire, but has recently undergone restoration that has been sympathetic to its heritage and been reopened as a pub and restaurant that has been incorporated into a new development of apartments and offices. A couple of minutes walk away is the Kings Arms, again Grade II listed and a fine example of Victorian pub architecture, dating from 1879. The Black Lion Hotel on Chapel Street reopened in May 2016 after refurbishment and stands out with a rather imposing curved frontage. The Egerton Arms Hotel, on Gore Street and close to the current Salford Central railway station has occupied the site since the early 1840s. The current building is a red-bricked Edwardian two-roomed local bar. In the heart of historic Bexley Square, we can still visit the New Oxford. Dating from the 1830s, it remains a popular and award-winning establishment.

We end with a true Victorian pub on Liverpool Street, the Union Tavern. Dating from the 1850s it remains a Joseph Holt pub, and visitors are reminded of the local pubs lost to demolition and closure with an array of pictures that adorn its walls. Hopefully, these remaining examples will survive many more years in retaining the pub heritage for future generations.

[i] Return of Licensed Houses for 1901 (P.P. 1902, (408)).

[ii] Manchester Evening News, 29 November 1950.

[iii] The Guardian, 9 September 1959.

[iv] Manchester Evening News, 5 March 1954.

[v] The Guardian, 7 April 1960; The Guardian, 8 May 1958.

[vi] The Guardian, 20 January 1961.

[vii] The Guardian, 13 April 1961.

[viii] Cowan, F., History of Chesters (Swinton, 1982), p, 28.

[ix] Richardson, N., History of Joseph Holts (Swinton, 1984), p. 23.

[x] Richardson, N., Salford Pubs (pt. 3) (Swinton, 2003), Kindle.

[xi] Richardson, N., Salford Pubs (pt. 3) (Swinton, 2003), Kindle.

I found this article very personally interesting. My parents were licencees of The Kings Arms in Ellor Street from approx 52 – 1959. It was extremely busy. Tetley’s was the brewery. I well remember The Whit Week walks when all the customers would cheer us on.