Stakeholder requirements

The project began by defining the current state of the art and the stakeholder requirements for product sound quality. We carried out a survey of manufacturers, both SMEs and larger companies, within the UK. We also talked to consumer organisations, and those representing the elderly, hearing and visually impaired.

Establishing stakeholder requirements

Who was contacted?

Initially a simple postal questionnaire was carried out in order to establish the perceived relevance of sound quality assessment in a variety of industries. Questionnaires were sent to one hundred UK based manufacturers of a wide variety of different types of products.

The types of product included in the survey, and the categories used to display the results are listed below:

Outdoor Equipment Domestic Appliances and White Goods Heating and water Home entertainment

Mowers (domestic and commercial), and engines

Outdoor tools

DIY tools e.g. Electric screwdrivers, drills, multi-tools, circular saws, jigsaws, etc.

Microwave

Vacuum cleaner and floor cleaning equipment (domestic and commercial), floor polisher (domestic and commercial), steam cleaner

Extractor hood for oven, small kitchen appliances e.g. juicer, ice-cream makers, steamer, slow cooker, fryer, can opener, bread maker, kettle, food processor, whisk, food mixer/blender, coffee maker, etc.

Fridge (domestic and commercial), freezer, cooker, washing machine, spin dryer, tumble dryer, dishwasher

BBQ, Hostess Trolley, Gas and Electric fire

Hair dryer, commercial hand dryer , electric toothbrush, electric shaver, trimmer and hair remover, massager

sewing machine

Heater (domestic and commercial)

Heating stove

Air conditioning equipment (domestic and commercial), ventilator (domestic and commercial), fan (domestic and commercial), dehumidifier (domestic and commercial)

Electric blanket

Shower, water pump, catering and heating boiler

Computer, projector, camera, camcorder, video recorder, DVD player, TV, mobile phone and associated equipment (e.g. hands free kit), photocopier, scanner, fax machines, printer

(All products are for domestic use unless otherwise stated)

Forty seven questionnaires were received from companies, in all of the categories listed above, though not all of the specific types of product were covered by the replies. One of the questionnaires was incomplete and so the results from this have not been included. Two companies sent two completed questionnaires from different employees, and one manufacturer sent three completed questionnaires from different employees, since the replies in each case were slightly different, none of these questionnaires have been removed from the results.

The written questionnaire summary

The replies to each question received from all of the manufacturers is summarised below.

Is the loudness or quietness of your products important to customer satisfaction? And do you think that the sound quality of your products is important to customer satisfaction?

Respondents were asked to ‘tick one box’. When asked is the loudness or quietness of your products important to customer satisfaction 50% of respondents answered ‘always’ and a further 37% answered ‘often’. In reply to the question ‘Do you think that the sound quality of your products is important to customer satisfaction?’ 46% also answered ‘always’ and a further 24% answered ‘often’. Only one manufacturer returned the answer ‘never’ in response to the question on sound quality.

This lends support to the idea that a significant proportion of manufacturing companies rate sound quality as an important factor when investigating the acoustic emissions of products. Interestingly one manufacturer said they considered sound quality as ‘always’ important to customer satisfaction whereas loudness was only ‘sometimes’ important.

When do you typically consider the loudness of a product, in the design cycle? and when do you typically consider the sound quality of a product, in the design cycle?

These questions were designed to reveal when loudness and sound quality were considered in the design cycle of a product, and respondents were asked to tick ‘as many boxes as apply’. From the replies 59% of the respondents said they considered sound quality at the ‘early stages of design’ (76% of respondents considered loudness at this stage), 48% ‘once a prototype is produced’ (54% said they considered loudness at this stage) and 37% at the ‘end of product development’ (more than the percentage that said they considered loudness at this stage which was 33%). Only three companies selected the options ‘sound quality never considered’ and one manufacturer selected ‘sound quality not important’. None of the companies ticked the boxes ‘loudness not important’ or ‘loudness is never considered’.

The majority of the respondents answers fitted into three categories. Those that considered sound quality: at the early stages of design (28%); once a prototype is produced (15%) or at all three stages of the design cycle (22%). Companies that returned the reply ‘other’ for consideration of sound quality were further investigated by including them in the list of manufacturers selected for telephone interview (see below).

If you carry out sound quality assessment, how is this done?

The three answers to this question are shown in the diagram below along with the ‘other’ option; once again respondents were asked to tick ‘as many boxes as apply’. Three companies had answered sound quality is ‘never considered’ to the previous question and therefore didn’t reply to this question. The two most popular methods of sound quality assessment were found to be ‘informal listening by the designers’ (63%) and ‘accessing acoustic signals on instrumentation’ (72%).

48 % of respondents only used one method of sound quality testing. The two major categories being 17% of respondents who said that they used ‘informal listening by the designers’ alone (although two of these had also ticked the ‘other’ box), and 28% who said that they relied on ‘accessing acoustic signals on instrumentation’ alone (although one of these companies had also ticked the ‘other’ box).

46% relied on more than one type of testing for sound quality in two major groups: 28% said they used a combination of informal listening by designers and accessing acoustic signals on instrumentation and 15% said they used a combination of all three options.

What effect did manufacturer size have on the test methods used?

Formal tests using independent juries was not used by any companies with less than 100 employees. Whereas 21% (five of the twenty four) companies with 100 to 1000 employees and 36% (four of the eleven) companies with more than 1000 employees used formal testing with independent juries.

The five companies that had selected the ‘other’ option for sound quality assessment were further investigated by including them in the list of manufacturers selected for telephone interview (see below).

Following up the written questionnaire

The written questionnaire was followed up with telephone interviews of a selection of the companies. The time consuming nature of the telephone interview process placed limitations on the number of companies selected for telephone interview. Therefore this stage was not intended to give a representative cross-section of the role of sound quality throughout the whole of the UK’s manufacturing industries. Instead the companies interviewed were chosen in order to investigate areas in which manufacturers appeared to demonstrate an enthusiasm about sound quality and its potential applications despite it not already being an established requirement of the product, or to investigate areas in which little sound quality research has been documented. Companies were also chosen to investigate opinions on sound quality in SMEs. The nature of the semi-structured interview strategy allowed this smaller sample to be examined in more depth.

Replies by category

Domestic appliances, white goods, heating and water

Firstly heating and water is considered as a single category and secondly domestic products and white goods are considered together (several of the companies manufactured both types of product). The heating and water category contained manufacturers of all sizes, but the domestic products and white goods category mainly contained manufacturers with more than 100 employees.

Is the loudness or quietness of your products important to customer satisfaction? and do you think that the sound quality of your products is important to customer satisfaction?

The only manufacturer that returned the reply ‘never’, when asked whether sound quality was important to customer satisfaction was in the heating and water category.

Go back to the written questionnaire summary

When do you typically consider the loudness of a product, in the design cycle? and when do you typically consider the sound quality of a product, in the design cycle?

One manufacturer in the heating and water category said that sound quality is ‘not important’ and one manufacturer said it is ‘never considered’. The other two manufacturers that said sound quality is ‘never considered’ were in the mowers and outdoor equipment category. None of the manufacturers in the domestic appliances and white goods category said that sound quality was ‘never considered’ or ‘not important’.

Go back to the written questionnaire summary

If you carry out sound quality assessment, how is this done?

A high percentage of manufacturers in the domestic products and white goods category (27% compared to 20% for all of the manufacturers) said that they carried out formal tests using independent juries. This is possibly because these types of manufacturer were all medium or large companies (i.e. with more than 100 employees). Conversely the percentage of manufacturers of heating and water products doing formal tests using independent juries was very low (5% compared to 20% for all of the manufacturers). Most of the manufacturers which said they carried out formal jury testing were further investigated by telephone interview. Interestingly, the percentage of manufacturers using the sound quality method ‘informal listening by the designer’ was also very high (82% compared to 63% for all the manufacturers) in the domestic appliances and white goods category and low in the heating and water category (50% compared to 63% for all the manufacturers).

Telephone interviews

Twelve companies and other stakeholders such as consumer groups were selected for semi-structured interviews. The companies manufactured outdoor products, domestic appliances, air conditioning and heating systems, electric showers and audio-visual equipment. The written questionnaire replies of the selected companies are summarized below (click on image for larger version):

Fig 1. Summary of written questionnaire results for companies selected for telephone interviews

All except one of these companies considered that their products are important in terms of loudness and sound quality. Answers to the written questionnaire were used to generate subjects to be explored in the semi-structured interviews. Topics covered during each interview included:

- Background questions on work role of interviewee, the size of the company and the products manufactured in the UK.

- A definition of sound quality and how this relates to products manufactured by the company.

- Methods of sound quality testing used and how this is related to the design and manufacturing process.

- What is the target sound? How is this decided?

- Customer feedback, including consideration of aging population and people with disabilities, standards and labelling.

- The future of sound quality testing in the domestic appliance market, and any other considerations highlighted by the interviewee.

In summary, small and large companies rely on a good work relationship between their marketing and consumers departments as the sound quality of their products is becoming increasingly important to their customers. Sound quality is mainly viewed in terms of noise level and annoyance. Perceptual testing is not usually rigorous instead it is carried out using informal listening by designers, or jury tests using staff and sound quality indices are not usually considered. The industry appears to welcome an approved standard method for sound quality testing. Consumers associations, consider criteria relevant to consumers which relate to the product as a whole; the ease of use, some key features and convenience, for example. Sound quality is mainly only considered for sound reproduction products.

Manufacturers’ options

Definition of sound quality and products manufactured by the company

Manufacturers were asked to differentiate loudness from sound quality. Loudness was mainly identified with the sound pressure level and sound quality was understood as an irritant noise, a rattle, a tone or an excessive whine. Manufacturers of air conditioning, some manufacturers of outdoor products and some of white goods mentioned sound that is pleasing to the ear, or sound that does not interrupt a normal conversation.

Manufacturers do not assess automatically the sound quality of their products. They only do it when they develop new products on a large scale or when a significant number of complaints from customers take place. Changes in legislation e.g. the Environmental Noise Directive for outdoor products may drive a manufacturer to take a greater consideration for sound quality assessment. It was also suggested by one manufacturer that sound quality could help Small Medium Enterprises (SMEs) to compete against bigger competitors.

Methods of testing and the design and manufacturing process

When asked about considering sound quality at the early stage of product design interviewees replied that good sound quality begins with a good selection of components. However, all stressed that sound quality evaluation is an ongoing activity throughout product design, that it is impossible to say what sort of noise is going to be developed at the drawing board stage and that a prototype is necessary to carry out experiments. Sound quality assessment at the design, construction and testing stages is often carried out according to the manufacturers own experiences or standards.

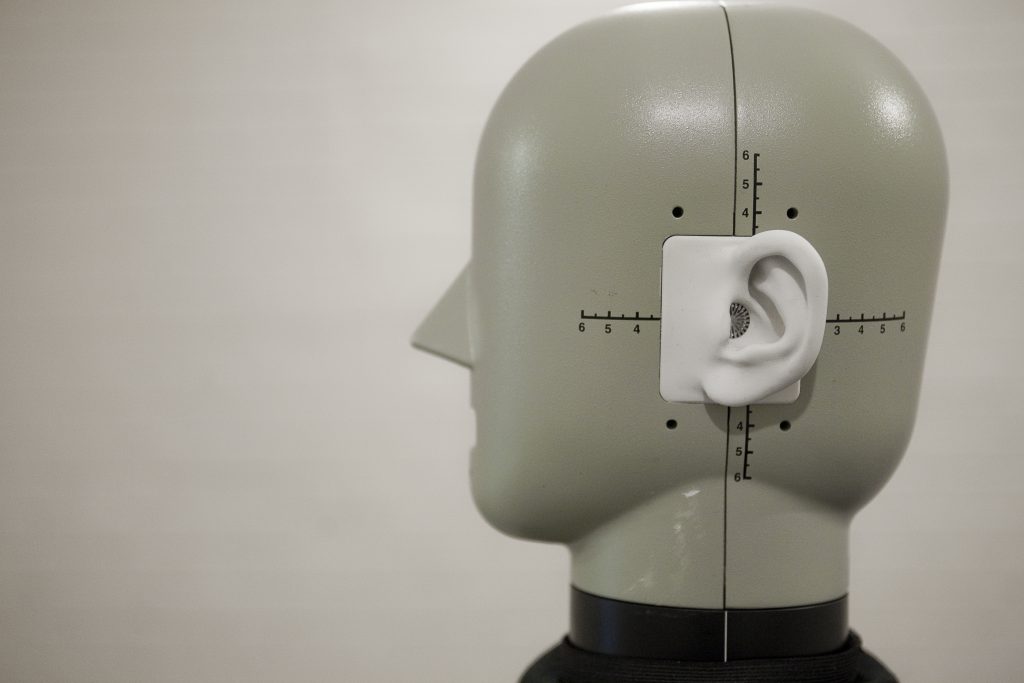

Objective testing is usually crude. Testing is carried out by placing the product in a ‘sound’ room or in some other part of the factory with low background noise. The product is set to perform its normal functions as well as under extreme conditions. The sound level meter is used to obtain a range of figures in dB(A). Only a few companies mentioned using FFT analyzers to try to locate the cause of the annoying sound. One manufacturer mentioned using Cool Edit to hear how the sound would be after removing specific aspects of the noise spectrum.

Perceptual testing is used to pick up information that objective measurements would not. These tests tend to take place when the designers, engineers and quality technicians test prototypes of their product and an opinion of the sound is expressed. Identifying noises which create annoyance or have the potential to make customers believe the product is not working, for example. A shower manufacturer commented that it is also important to take account of the product’s connections with its surroundings as these could also potentially be another source of noise.

Jury testing is also carried out by manufacturers of outdoor products, white goods, air- conditioning and manufacturers of audio-visuals. Again tests often are carried out in rooms of low background noise or a ‘typical’ room such as a kitchen, an office, a domestic room or outside may be selected for tests of the product in situ. The testing panel usually consists of employees of the companies and sometimes of customers. The size of the panel appears to be less than 10 people and the jury is untrained.

It was found that different versions of the jury test are carried out:

- In the case of outdoor products, the manufacturer will consider the noise at ear position of both a user and an observer;

- Some manufacturers don’t ask specified questions but instead gauge people’s reactions when the product is switched on specific settings;

- Some manufacturers invite customers to use the products in their houses and complete a questionnaire;

- One company made the comment that to access customer’s opinion, they ask questions at retail outlets;

- There are other manufacturers who consult tests made by consumer associations rather than conduct their own jury test, because they provide a comparison with the competitor’s products.

Most of companies could not stipulate the exact amount of time taken up by sound quality, as the activity often is carried out during tests on the overall functionality of the product. Though all said only a small percentage of time is spent at present. Two manufacturers commented that subjective tests are faster than objective tests. The current process is reckoned to be reliable because of the low number of received complaints.

What is the target sound?

A product is considered aurally suitable when:

- It has a low sound level or the product noise is quiet;

- Adverse noises are non-existent;

- It is a good sound;

- It sounds better than the competitors’ products;

- Subjects give positive comments.

Customer feedback, standards and labelling

Manufacturers of appliances were asked to express opinions of their customers knowledge of sound quality.

58% of the companies thought that their customers know what they want from their products, while 42% thought they don’t. When asked about how customers would like their product to sound ideally, 83% said the customer would like their products to sound as quiet as possible. But 17% of the manufacturers acknowledged that quietness is not always that good, because the sound of the product is a source of information and part of the identity of the product. Furthermore when a product such as a hedge trimmer is quiet, it can become a dangerous tool. One manufacturer gave an example of a quiet vacuum cleaner for outdoor use. The vacuum was found not to be successful with the customers because they thought it was not working. They therefore preferred a product with a good sound rather than a quiet sound.

The manufacturers were also asked if they considered ageing and/or disabled populations when doing sound quality assessment. All disregard them with the exception of one manufacturer, who considers the possible interferences between the sound of their product and hearing aids. Such consideration was given because of the personal experience of the designer. Overall there is very limited consideration of the ageing population and people with audio or visual impairments.

None of the companies interviewed were required to comply with consumer sound labelling and regulations (except the regulations for outdoor products) manufacturers. However 60% had their own internal standards. In general the manufacturer’s opinion on sound labelling is relatively poor. They are fully aware of the energy label, however none mentioned:

- ‘Blue Angel’ labelling in Germany: German Institute of Quality Assurance and labelling (RAL), (Deutsches Institut für Gütesicherung und Kennzeichnung)

- Federal Environment Agency, Germany

- The ‘Ecolabel’ European label, Regulation (EC) No 1980/2000

- Sound labelling for computers used in Sweden

Manufacturers of outdoor products have strongly expressed that the dB is poorly understood by consumers. The manufacturers therefore are in favour of a change from sound power label in dB(A) to a sound quality label.

The future

Appliance manufacturers consider sound when identifying an annoying sound, but most of them do not look at the sound quality of their product, in a similar way to a car manufacturer. This means they are not after a sound that is, for example, sportive, robust or sharp. Measurements are already considered to be adequate; however, design teams often do not include an acoustics expert. This would explain why so few companies consider using FFT analysers. They also are unaware of the existence of software for sound quality. There appears to be a big gap between current practice in the UK and state-of-the-art sound quality assessment. However, state-of-the-art practices are relatively expensive. Attitudes towards sound quality assessment would also change if the product sound could be heard before purchase in the retail shop (as in the automobile/audio industry) or on internet.

Some companies would like to know how to use an FFT analyser to understand the noise of their product better and have access to rooms with defined acoustics. Others suggested access to some software for sound quality. With the exception of two companies, manufacturers seem to be unaware of psychoacoustics indices, but all agree that although sound quality is not directly measurable it can be described by adjectives and by answering carefully worded questions.

Consumers Associations and Sound Quality

The Consumers Association usually looks at criteria relevant to consumers which relate to the performance of the product, ease of use, some key features and convenience. Sound quality is mainly considered for sound reproduction products because the sound is fundamental. When asked about sound quality of domestic appliances, they require them to be as quiet as possible with no annoying sound.

Associations representing people with hearing impairments consider the sound quality of some products without calling it ‘sound quality’. For example, they will create products which could be heard by people with hearing impairments such as alarm systems, ring tones on the phone or car indicators. Other products on the market can be modified in order to function better for deaf or hard of hearing (H-of-H) people, but this could involve a visual rather than aural modification. In the future, they would like to see products useable by everyone in society. In the case of the visual and hearing impaired, the product ergonomic is mainly considered rather than the sound quality. Some specific projects between the association and the manufacturer do take place where sound modifications can be done, but this is the exception rather than the rule.