This is a guest post from Professor Chris Hopkins, Emeritus Professor of English from Sheffield Hallam University where he was Head of the Humanities Research Centre from 2003 until 2020. Chris works mainly on British writing between 1900 and 1950, with particular interests in working-class writing, women’s writing, Welsh writing in English, writing of World War 2, and popular fiction. In this post Prof Hopkins discusses how the Salford-born writer Walter Greenwood, author of Love on the Dole, responded to the changes in the built environment of Hankey Park, where his novel was set.

Walter Greenwood became a famous son of Salford, born into a family whose precarious economic state worsened after the death of his father, a hairdresser, when Greenwood was nine-years old. After leaving school aged 13, Walter worked in many low-paid jobs, including a pawnbrokers, a draper’s shop, the Ford factory at Trafford Park, and dismantling wooden packing cases. Then came the Depression. From 1928 to 1932 Greenwood was on the dole and began writing first short stories and then a novel about life in Hanky Park, the area of Salford where he lived. Greenwood and his family could hardly believe it when his novel, Love on the Dole, was accepted for publication in 1932, coming out the following year. The book was an immediate success, showing readers who didn’t know what it was like to live in the insecurity of long-term poverty. Even more successful was the play version, co-written with the Manchester writer Ronald Gow in 1935, and ever since then Love on the Dole, Walter Greenwood, and Salford have been remembered together. Though Greenwood wrote later novels about other places his first and last books were firmly set in Hanky Park, a place he could never completely leave behind. This blog is about how Ellor Street was replaced by Walter Greenwood Court (and two other skyscrapers), and by what we know about the writers reactions to these transformations.

Not that many writers have buildings named after them, let alone writers with working-class roots, and even fewer then suffer the indignity of the dedicated building being demolished within 35 years of its completion (though 27 years after Greenwood’s death at least). For that period (between 1964 and 2001), Walter Greenwood Court was a monument (or anti-monument) to Greenwood’s account of life in Hanky Park, and in itself an example of the very different kind of housing which it was thought should replace it – a strand of post-war thinking about city-planning made concrete. As the building’s demolition in the second year of the 21st century suggests, its success as a response to long-term poor housing in many parts of Salford was not for all time, and indeed it was regarded and experienced in a range of ways over the 37 years it was lived in by Salford citizens.

Walter Greenwood Court was one of three ‘high-rises’ built in Salford in the early 1960s as part of a very long-awaited redevelopment to replace housing in the slum area often known as Hanky Park, which had been repeatedly judged inadequate by social commentators and housing inspectors from at least as far back as the 1930s. (1) The other two high rises were Eddie Colman Court and John Lester Court. Eddie Colman was born in Ordsall, Salford, and played football for Manchester United from 1952 until his premature death in the Munich Air disaster on 6 February 1958. John Lester seems less well-remembered, but I think he must have been the John Lester who was Mayor of Salford in 1955-6. Both Eddie Colman and John Lester Court still stand, and are now in use as privately-owned accommodation for students at the University of Salford.

As early as 1954, the Manchester Evening News headlined an article, ‘ “Skyscrapers” to Go Up Soon?’ (16/11/1954, p.5). By 1958, the Manchester Guardian could confidently announce in its headline: ’15-Storey Flats for Salford – a New Hanky Park’ (30 August 1958, p.10). The month before the same paper had published a short item about families from Ellor Street living in houses due for demolition who strongly wished to be rehoused in the same area:

People in the Ellor Street area of Pendleton – Hanky Park in Walter Greenwood’s Love on the Dole – have insisted on staying in Salford when three-hundred houses are demolished. So many have refused to go to Little Hulton [a low-rise ‘overspill housing development a considerable distance away] . . . that the city is to build 15-storey flats in the area, it was announced today. (30/8/1958, p.8).

Shortly before that the Manchester Guardian reported on a legal appeal by a handful of Ellor Street householders who felt even more strongly and wanted to make the case that their houses were fit for continued habitation. Again, the link to Greenwood and Love on the Dole featured strongly in the article ‘Love on Dole Street Visited – Clearance Enquiry’:

After a public enquiry at Salford yesterday, a Ministry of Housing Inspector visited the little street on which Walter Greenwood, the Salford-born novelist, based his book Love on the Dole.

Earlier . . . the Inspector heard an appeal by thirteen objectors against a compulsory purchase order by the city council affecting 329 houses, two public-houses, three shops and three other buildings in the Ellor Street No.1 area, which in his book Greenwood named ‘Hankey Park’. . .

Dr J.L. Burn, the city medical officer of health said that all the houses in the area were unfit for habitation and there was serious overcrowding. The houses were at least a hundred years old and everywhere there was visible evidence of decay; in only eighteen was there provision for hot water [and] the most unhealthy feature was dampness (June 26 1958, p.26).

After due consideration, the Enquiry clearly ruled against the objections and supported the critical views of Dr Burns about the fitness of Ellor Street to meet contemporary ideas of adequate housing.

Much reporting of the new development linked it to Greenwood or Love on the Dole. Salford Corporation even marked the association between author and place by presenting Greenwood with the no-longer needed ‘sixty-year old wooden name-plate from Hankinson Street, Pendleton, which gave its name to Hanky Park … the street is being demolished under a slum clearance scheme’ (The Guardian, 10 March 1960, p.18). I wonder what happened to that Street sign? Once the clearance of the old Hanky Park was completed over the course of a decade, and the new tower-blocks built and ready to be moved into, there were some admiring reports at the time and later. For example, in 1983 an article by Louis Herren in the Illustrated London News about redevelopment across Britain saw the Salford work as a long-term success:

If Cobbett and Orwell could have come with me [on a tour of Britain’s once poorest cities] . . . they would have been astonished by Hanky Park in Salford, one of the more distressed cities in the north-west. This was the terrible slum which Walter Greenwood wrote about in Love on the Dole, but it is now a well-planned housing estate with a good shopping-centre, pubs and a balanced mix of high-rise and conventional housing (‘Louis Herren’s Rides’, 1 May 1983, p.36).

Insider views were more mixed and while starting off positively, became less so over time as interviews quoted on Municipal Dreams suggest (2):

We would have preferred a house, but now we find that we really like living in these flats, I think that they are lovely and the rents are fair

Dorothy Huckle, c1964

All my friends moved to Ellor Street, which was all high-rise 70s flats and a new shopping precinct built all out of concrete. It was rotten, horrible; like a concrete wasteland. And that was when it opened

Peter Hook, 1970s

A BBC North documentary, Close Up North: Love on the Dole, was filmed in and around Walter Greenwood Court during the early 1990s. By that time, the tower-block was in temporary use as a hostel for homeless young people, and the documentary implicitly and movingly compared their contemporary poverty with that of those living in Hanky Park in the 1930s (3). Though these young people lived in better housing than Hanky Park offered (even towards the end of the declining life of Walter Greenwood Court), they were still all on the dole, with no permanent address, and early pregnancy and trouble with the Police seemed common. In short, like their predecessors of 60 years before, they were still suffering from the effects of being bought up in poverty and had no long-term plans. The documentary probably contains some of the few and last filmed images of both the interior and exterior of Walter Greenwood Court.

There are a few comments made by Greenwood himself about the high-rises which replaced the streets and housing he grew up in. His memoir, There Was a Time (Jonathan Cape, 1967) mainly recalls the years of his youth, between his birth in 1903, and 1933, the year in which he published Love on the Dole. The final chapter though does comment on the recent redevelopment of Salford:

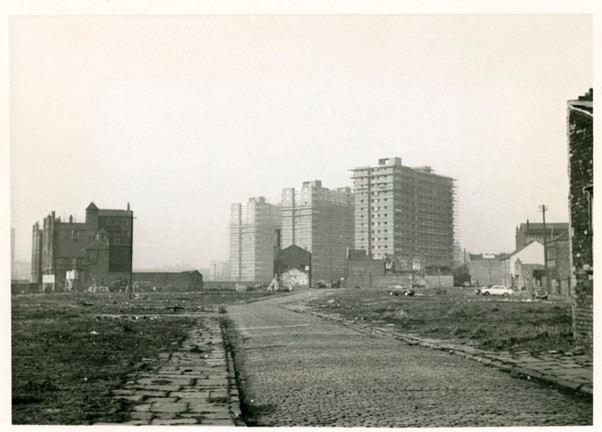

Bulldozers are at their work of destruction here . . . It has the face of a battlefield . . . street upon street of little houses, corner shops and pubs crashing into heaps of rubble. Bonfires of front doors, window frames and floorboards; funeral pyres as it were of ang age that is no more. Where the wreckers have finished their work only the cobbled roadways and pavements remain to mark the streets which were our childhood playgrounds and where our homes had stood (There was a Time, p. 250)

There is a hint of nostalgia here – after all this is part of his own past being bulldozed. But the next sentence puts that sentiment in its place:

[These houses] were built when the British Empire was at the pinnacle of its wealth and power, and they had sheltered defrauded generations for whom life had been an endless struggle both insulting and deprived.

There was a Time, p. 250

‘Defrauded’! Greenwood knows that the wealth of the Empire never reached Hanky Park, no more than it did the then subjugated and colonised people who helped produce it. However, further paragraphs do see positive developments in British society of kinds linked to the post-war urban redevelopment schemes – there are transformations and opportunities for some at least:

Already the builders are working alongside the wreckers. Steel skeletons of the multi-storied flats are now rising gaunt above the sky-line, the world of tomorrow springing from the ruins of yesterday. When completed the old neighbourhood will have changed its ancient name of ‘parish and ward’ for ‘precinct’ (There was a Time, pp. 250-1)

A sudden flowering; meritorious children of my contemporaries, now adult, are graduates of Oxbridge, Red-brick and the local school of Advanced Technology. Yesterday the Depression and lo! By a hop, skip and jump the Space Age and a Welfare State. A five-day, forty-hour week, holidays with pay, superannuation pension schemes, lunch vouchers and works’ canteens … (There was a Time, p. 251)

However, his comments from the 1970s seem slightly less optimistic. In his last and unpublished novel, It Takes All Sorts, there is a relatively neutral but not exactly enthusiastic description of Manchester and Salford as they undergo development, linked to the viewpoint of the character Minnie, but sounding more like a narrator’s voice:

Mid-twentieth century town-planning had razed great tracts of slumdom leaving no-man’s lands on whose windy deserts could be seen in completed, preliminary and advanced stages of building the multi-storied flats and the motor ways, some elevated, which would make up the face of tomorrow’s city. (4)

This could be a description of the early 1960s photograph above, where the three tower-blocks do stand alone in what could rightly be called a waste-land. A few other responses from him showing a similar ambivalence are recorded in his 1973 Kersal Flats interview. Parts of this are filmed in front of Walter Greenwood Court, and though Greenwood makes no reference to the building named after him, he does make clear that while he thinks Hanky Park had very inadequate homes, and that the welfare state had greatly improved the quality of working-class life, he thinks that there has nevertheless been a loss of community in the new Salford and links this to the new high-rises. (5) In short, while Greenwood fully saw the utter inadequacy and poverty of housing in Hanky Park and was glad to see it go, he had some doubts about the high-rise replacements, and perhaps a tiny amount of nostalgia about the urban environment he grew up in. He never lost his belief that the intolerable life of Hanky Park had improved after the Second World War, but he clearly sometimes wondered if those improvements would last. (6)

Notes

(1) See for example quotations from the 1930s and a housing inspector in the 1940s on John Boughton’s excellent Municipal Dreams blog on the Ellor Street development ( 8 October 2016). See the next blog on the same site for further discussion of responses to the new housing.

(2) The first quotation is from Salford Online, and is cited on Municipal Dreams. The second quotation comes from this blog-site as well, but its original source is not so clear.

(3) The documentary was directed by Lyn Webster Wilde, Halcyon Productions, broadcast 1 December 1994; a copy is held in the Salford University Archives Walter Greenwood Collection, WGC/7/18/3.

(4) The Walter Greenwood Collection in the University of Salford Archives has a number of manuscript and typescript drafts of this novel, which Greenwood was working on from the late nineteen-sixties until at least 1970. This quotation comes from WGP1/28/1, identified on the Archive hard-binding as ‘ It Takes All Sorts, E Carbon Copy’, Chapter 2, p.7.

(5) See: Walter Greenwood: the kersal flats.co.uk Interview (1973)

(6) An earlier but I think less good version of this blog was posted on my Walter Greenwood blog-site!

Thank you for this very interesting literary evocation of the Pendleton Estate and your kind words on the Municipal Dreams blog. FYI, the Peter Hook quotation (footnote 2) was taken from ‘Pendleton Together, An Ideal for Living’, a glossy brochure published by the consortium that redeveloped the estate, not dated. I have a copy but it’s no longer available on the internet.

Many thanks John – the Peter Hook info is very helpful. I’m following Municipal Dreams with great pleasure. Really informative commentary + photos.

– Best Chris.

A fascinating read. Thanks very much.

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More: hub.salford.ac.uk/modern-salford/2022/08/26/from-love-on-the-dole-to-walter-greenwood-court/ […]