By Sally Halsall

It was every mother’s nightmare, screaming for help but no one came to help. My lovely vulnerable son. I knew there was something wrong and the only person who could save him was me. But he did not seem to listen to me when I tried to steer him in the right direction. Everyone else had given up, the authorities had cast him out. He had not been educated since he was expelled from school at aged 11, social services were only interested in blaming the mother and after a decade of trying to get an assessment the psychologist took the easy route, suggesting he probably had depression because of my split with his father.

The problems start when he was just 2 with tantrums which went on and on. I thought the only way to understand Alex would be to study psychology, so I started what turned out to be a very long journey. It was around this time that for several weeks Alex kept vomiting and we saw his weight drop. The Health visitor called it ‘failure to thrive’ and all the time my instincts were screaming that something was not right with Alex. No matter how many times we visited the GP we did not get referred to anyone until eventually he projectile vomited across her consulting room. She immediately sent my husband and I to A&E with a sealed letter. I opened it and felt a lump catch in my throat when I saw the words ‘Alex Henry’s mother is doing well since she returned to education’. I knew this was code for ‘she is not making it up’. I’ll never forget that.

Alex did well at school until at aged 6, he complained of being bullied. The head teacher agreed to keep a classroom unlocked so that Alex had a ‘place of safety’ to go to but shortly afterwards following an incident in the playground Alex found the classroom was locked. After that he developed terrible anxiety and would not go into school in the mornings, running through the playground and clambering the high walls to try to escape. The Educational Psychologist refused to see him but after pestering her with phone calls I received a crumb from her table. She said, ‘he has probably developed a school phobia’.

The Catalyst

It was around this time when Alex was 7, that my marriage to his father broke up. His teachers were becoming increasingly frustrated at him. I remember one teacher complained to me that he would not sit down in the classroom and constantly disrupted the class by marching around the classroom. I remember the way she spoke about him was as if she loathed him. I wondered if he sensed that and if the teachers were bullying him too. The final straw came for Alex when another teacher yelled at him in front of the class ‘just because your parents have split up does not mean you do not have to do your homework!’ He looked destroyed. That was the last day I made him go to that school.

Alex, Aged 9.

We were resolute, we would not take Alex back until he received the help he needed but instead we received threats of court action and fines. We eventually realised help was not coming and some months later when Alex was 8 his father paid for Alex to attend a local private school which was small and affordable. I remember the school sat with Alex on a one to one basis and very slowly and gently coaxed him into the classroom. He settled, and for the next year or so he seemed happier, made friends and seemed to enjoy his schoolwork.

However, as his last year approached before he would move to secondary school he started to have meltdowns again and the school were struggling with him.

It was at this time that things started to get worse. In a family photo he looked oddly at the camera, his eyes looked unfocused, like he was ‘punch’ drunk. He had more and more meltdowns and his grandparents would no longer allow him to visit. The Children and Family Court Advisory and Support (CAFCASS) had decided upon shared residency and so Alex moved from my home to his fathers during the week which disrupted his routine. He did not cope well with change and when he arrived at my house he was always anxious.

Meltdowns

His meltdowns would start in the evening, usually between 8pm and 10pm. He would come downstairs into the lounge and start to move objects around in a frenzy of worry. Immediately I knew he was going to have a meltdown but once triggered, nothing would calm him down. He would talk to himself in frightened tones becoming more and more distressed, slamming doors over and over, rearranging ornaments and furniture obsessively. This would worsen over several hours and eventually I would take him into my bedroom where he would continue to have a meltdown. His distress was painful and heart-breaking. With my arms and legs wrapped around him I would gently restrain him so that he could not hurt himself, telling him ‘It’s OK, mummy loves you’ over and over until finally in the early hours he would fall asleep in my arms.

Alex had been having meltdowns for 18 months when it reached its peak at several times a week. One morning, exhausted I rang NHS Direct who told me to take him into A&E where they had people waiting who could help him. I had to get help to force him into the car and once we arrived we were immediately ushered into a room. All the time I was aware of the cameras in the room and I knew they were observing me. I was terrified they would blame me. Alex was saying he was an ‘alien’ and rushing at the door to try to pull the door open. I put my foot by the door and I remember it slamming ‘bang’, ‘bang’, ‘bang’. It seemed to go on for hours. Finally, help came but the nurse could not calm Alex down. The worst memory I have is of four male nurses holding his tiny screaming body down on the trolley while they wheeled him onto the ward. I kept wondering if I had done the right thing. Eventually he calmed down. His father came to see him. The consultant told us they had organised for a specialist psychiatric nurse to start an assessment the following day and I thought ‘hallelujah’. I left the ward for just a moment and when I returned his bed was empty. The consultant told me his father had discharged him against their advice. He didn’t want him labelled, he said. I was devastated.

By the time Alex was nearly 12 his meltdowns had stopped but depression appeared to overwhelm him. By this time, he had been transferred to a small private secondary school, but he was not happy, something or someone was upsetting him there. Then the day came when I received a phone call from his new school to tell me that he had been expelled because he had graffitied the school wall. It was not unexpected. I rang social services and they put me through to a man, but he did not seem to want to help and instead asked what Alex’s ‘tag’ was. Because they wanted to arrest him.

We pleaded with the local authority to allow Alex into the secondary school his sister Charlotte attended, but they refused. His father appealed against their decision and after several months the school were forced to accept him. We were jubilant and hopeful, and Alex was excited about being with his sister and other boys and girls he already knew. I remember thinking that Alex would have a chance to dream about his future again and a much-needed sense of belonging. But just 11 weeks later when Alex turned 13, I received a call from the Head Teacher informing me that Alex had been instantly expelled for ‘sexual misconduct’ after looking up a girl’s skirt. Alex did not seem to realise why this was wrong and kept asking why his sister could go to that school and he couldn’t. For the first time I could feel his huge sense of rejection and I was frustrated and angry because despite having completed my PhD in psychology I still did not know what was wrong with him and we were still getting nowhere. Trying, failing, trying, failing.

ASBO

During the day while I worked Alex moved between his father’s house to the streets, to the ‘alternative provision’ (study centre) and back to me. I did not know who his new friends were. I remember he stayed out all night and told me he slept on a park bench. By the time he was 14 he was involved in low level criminal activity. He was arrested for the first time for punching a bigger boy and charged with common assault. Soon I started to smell cannabis on him and it was not long before he was charged with possession. Eventually the Local Authority awarded him an ASBO to control his whereabouts, restrict his movements and impose a curfew. I did not realise at the time that this would be the catalyst for his prison life.

He came to stay with me less and less. The ASBO tried to parent him, to stop him going to a local estate and certain other roads and mixing with certain people. Every time he broke his ASBO, no matter how minor and despite it being a civil breach, he would immediately without a hearing or trial, be whisked into young offenders at Feltham and kept in isolation. Suddenly behaviour which would not normally be criminal, such as being seen with a certain person or walking through a housing estate, was criminalised and treated as an imprisonable offence, resulting in a long ‘criminal record’ and many months of his teenage life inside.

But the ASBO did not deter him, my love did not deter him, his father’s temper did not deter him. It was at this time I met and married Geoff, my second husband. Ex-RAF, no children of his own, loving and fair, I thought, this will give Alex the stability and role model he needs, and he will start to thrive like his sister. But instead Alex seemed to be going ‘backwards’. He had no interest in anything, his love of chess had by now totally disappeared, his concentration was non-existent, his social skills resembled someone who was not ‘with it’, even his gaze seemed odd.

Following one of his ASBO breaches the court ordered an assessment by an Educational Psychologist who said she could find no indication of anything wrong except possibly mild depression, and there were times when I started to question my instincts. I remember one day I tried desperately to talk to him, but my words seemed to run off him, like he was impermeable. I remember crying louder and louder until in the end I was standing in the kitchen, screaming, ‘please, please’, and his face looked pale and worried as he looked at me really confused because he just didn’t understand, and he said, ‘why are you so upset mum?’

By the time Alex was 17 he had been in and out of Feltham Young Offenders several times, usually for 2 months and always for breach of his ASBO. He had very little time out of his cell, usually locked up for 23 out of 24 hours, and was frequently put in isolation, sometimes for several weeks. There were frequent fights in the visiting hall in front of families, some of them children, and the prison guards were always slow to break them up.

Then when Alex was 19 his father, who was a self-employed carpenter, started to take him to work with him as his apprentice. Alex brought a girl home and they would spend evenings cuddling on the sofa watching movies and eating pizza and she loved him. I saw him often and months passed peacefully. They seemed happy. Finally, I had hope.

Alex and his mum.

That Fateful Day

Alex was 20. It was a hot Summer’s day on 6th August 2013 and Alex had been out shopping in Ealing Broadway with his best friend Janhelle Grant-Murray and Younis Tayyib and Cameron Ferguson. Janhelle and Younis decided to leave and go back to Younis’ address a few short minutes from the town centre. Whilst outside Younis’ address, Janhelle was confronted by a group of four older boys (Bourhane Khezihi, Taqui Khezihi, Dapo Tijani and Leon Thompson). The groups were strangers to each other.

Meanwhile Alex and Cameron had finished shopping and were making their way up the Uxbridge Rd to Younis’ address. Alex became aware that Janhelle was in an altercation with a group of boys. By this point Bourhane had removed his belt to use the metal buckle as a weapon and Janhelle had taken a bottle of wine from the local Cost-Cutters and was holding it down by his side.

Alex ran to Janhelle’s defence with Cameron running roughly 5 metres behind him. As he got to the scene he saw Taqui punching Janhelle repeatedly. Alex picked up Janhelle’s mobile (that had fallen from his pocket) and threw it at Taqui striking him on the top of his head. Bourhane punched Janhelle once and used his belt as a weapon, lacerating Cameron’s ear. Alex punched Bourhane once and Younis actively tried to prevent the violence. Dapo and Leon were passive bystanders and Janhelle punched no one.

The violence lasted under 40 seconds before Younis’ mum who had heard the noise and left her address which in turn stopped the affray. In that 40 seconds Cameron had put his hand inside his JD sports bag and held a knife. He never took the knife out of the bag and it was concealed at all times. He used the knife to stab both Taqui and Bourhane before fleeing the scene. At first Bourhane, Dapo and Leon said Alex and Janhelle also had knives, but these claims were withdrawn during their evidence and the pathologist report said it was possible that both knife injuries were caused by the same knife. No independent eyewitnesses saw the knife and it was suggested that the reason for this was because it remained concealed in a bag. The evidence emerged that no one present during the fight including Bourhane himself had realised there had been a stabbing. All boys dispersed before Dapo informed Bourhane that it looked like he had a scratch on his back. Taqui later died of his injuries. There was no evidence against Alex except for his presence.

The Aftermath

Later that day three police officers came to my door and told me they had received information that Alex might be in danger and they needed his mobile number. His father said Alex was staying with a friend and Charlotte reassured me that she had spoken with Alex and knew he was OK, but she seemed unusually quiet.

Two days later my husband and I had taken our motorhome to Pevensey Bay where we had arrived late in the evening. I remember it was pitch black and my husband was trying to fix the electricity when my mobile phone rang. The person on the other end of the phone told me he was the custody Sergeant from Croydon Police station and they had arrested my son for murder. They put me through to his cell. I remember the sounds of his screams echoing around the cell, barely able to hear me, like a small child again ‘I want my mummy’ over and over and I literally wanted to die. I went into a numb state, like I was on autopilot. I told my husband to drive us home. My daughter was distressed but worse than that she looked terrified. I reminded her Alex had said he didn’t hurt anyone but that’s when she explained that Alex had been charged with murder under Joint Enterprise, it didn’t matter who did it.

The next morning, we went to the Magistrates Court to hear the pleas. Alex’ girlfriend came, and it was that day she told me she was pregnant. Alex stood behind a Perspex screen, thin and pale next to his three co-defendants who towered above him. I tried to smile at him and mouthed ‘I love you’. The charges of Murder and GBH were read out to the first boy but everything stopped at the word ‘murder’, my legs had given way and I was on the floor, all I could hear were people saying, ‘is she alright?’ I thought it can’t get worse than this.

Alex returned to Feltham Young Offenders Institute on remand. During visits and I could still sense the brutal atmosphere. Fighting was so normalised in Feltham, there was a sense of nonchalance among the guards and I found it so hard not to be frightened. I asked him as he looked furtively around him, whether he had thought about what he might do when he got out. ‘I can’t think about that stuff mum. I can’t think straight’.

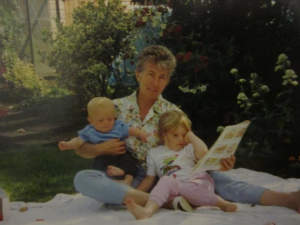

Alex as a baby in the garden with his grandmother and sister

During one visit Alex said to me ‘You know what the saddest thing is mum if I end up getting life? It’s that I know I won’t see nanna and papa again’. Since he was charged his grandparents health had rapidly deteriorated. I had to stay positive, I reminded him that he was only trying to help his friend, he didn’t hurt anyone, the jury were bound to believe him.

While Alex was on remand I joined the campaign group ‘Joint Enterprise Not Guilty by Association (JENGbA)’ and soon met other families of Joint Enterprise prisoners, some of whom had children under 16 serving life, some were not even present at the scene of the crime and many had learning disabilities. Gradually it dawned on me that this law was not about intention, or even about a fair trial, it was about catching the vulnerable in a net and throwing away the key. I knew I had to prepare Alex for the worst. The day came I had been dreading when he asked me again ‘Mum, what if the Jury find me guilty?’ and I said, ‘you will have to make a life for yourself in there Alex’. I wondered how I would carry on without him.

The grass roots campaign group Joint Enterprise Not Guilty By Association (JENGBA) put me in touch with a documentary maker who wanted to follow Alex’s case for the BBC documentary ‘Guilty by Association’. The director Fran Robertson explained that in recent years there had been so many examples of injustice as a result of Joint Enterprise and it was important for the public to see a case unfold. Like they all knew he wouldn’t get out. But it gave us a voice. Just in case, we thought.

The Trial

The trial started at the Old Bailey and the facts of the case were unravelled. We prayed that the boy who did the stabbing would change his plea and confess. I wanted to shout out ‘I know who did it!’ but what good would that do? I don’t have any evidence. I’m just another rubbish mum.

Days went past and still I willed the boy who had carried out the stabbings to confess, because then the charges of murder would be dropped, surely? On day four the Judge adjourned and when he returned Cameron Ferguson was asked to stand up. He was asked to state whether he pleaded guilty or not guilty to all the charges. ‘Guilty’, he said. I thanked God and cried. Because the parents of the victim knew who did it. And everyone knew it wasn’t my son.

The following night Alex became a father to a little girl and I cried. Every night we cried. Charlotte threw herself into her law books and I seemed to spend every evening trying to explain the law to disbelieving friends and family. Every morning it felt like the first day again. Like a punch in the stomach.

We listened from the public gallery as the prosecution painted a picture; an abstract work of art, it’s resemblance to anything real based merely on connotations. The jury were expected to make their decision based on inferences about the mental predictions of three young men in a 40 second spontaneous fight. I scrutinised the jurors, those 12 members of the public who would take my son away from his family and place him someone where he would spend the best part of his life on 23 hour-a-day- lockdown, 3 to a cell with an open toilet. Where he might think about killing himself.

On the Friday 7th March the jury went out to make their verdict. We had to sit outside the courtroom on the cold stairs and wait. At 3.30pm the following Wednesday the jury returned a verdict. The other courts were gradually emptied. We sat on the stairs and waited and prayed. I wondered why we had to wait so long. Other courts had announced verdicts but we had to wait until the Old Bailey was empty. And then the penny started to drop. We were ushered into the public gallery where we sat in the front row. I asked a friend to stand the other side of Charlotte as she might collapse. But Charlotte looked at my friend and they stood either side of me holding my arms. The jury looked pale. They didn’t look up at us like they normally did. The young girl who always gave a quiet smile looked like she had been crying. The older lady who looked so wise. The man at the back who looked so fatherly. The superior woman at the front who looked full of gleeful satisfaction every time she passed the judge a question and so affronted when one was declined (‘did you approve of your son’s friends?’ she attempted to ask Younis’s mother as she stood on the witness stand).

The Judge looked up at us gravely. ‘You will listen to the verdict in absolute silence. I will not tolerate anything but absolute silence from the public gallery’. The lead juror stood to read out the verdicts. Younis Tayyib was asked to stand. He was found not guilty. The Judge asked Alex to stand. He stared straight ahead, like he had had the life kicked out of him. His short fine frame, face pale like death. ‘Guilty.’ I looked at Charlotte. Like being under water. The words were muffled. I looked up at Charlotte again. ‘Did he say guilty?’ I felt my body falling. ‘I can’t hear him’ I remember trying to say in great gasps, but I couldn’t lift my head. ‘Yes Mum he said guilty’. I covered my face and wanted to die right there, right then. I looked up from where I was now curled up on the floor ‘What for?’ ‘For all the charges mum’. And then Janhelle’s mum was wailing ‘you can’t take my child’ and I could feel the hands of the security officers who were trying to remove me.

Alex was sentenced on 28th March 2014. During sentencing Charlotte and I held on to each other tightly and told each other we would fight and fight. I would not look at the Judge, I did not want him to see me cry. The Judge looked directly at Charlotte as he sentenced her brother to 19 years in prison. I have never felt so angry in my life, but I did not let the Judge see me cry. All I could think was I had let my son down and now my vulnerable beautiful boy was taken from us all.

Read the continuing blog – Fighting for my brother, by Alex’s sister Charlotte here.