‘Fathers have a substantial impact on child development, wellbeing, and family functioning, yet parenting interventions rarely target men, or make a dedicated effort to include them’ (Panter-Brick et al., 2014: 1209).

The Rarity o f Parenting Programmes for Fathers in the United Kingdom

f Parenting Programmes for Fathers in the United Kingdom

The Fatherhood Institute (http://www.fatherhoodinstitute.org/) highlights the need for family services to target fathers directly given that fathers are remaining marginal and overlooked in family interventions (McAllister et al., 2012). Father are hard to recruit into voluntary parenting programmes. It is predominantly mothers who engage in Parenting programmes and also evaluate them (Salinas et al., 2011; Glynn & Dale, 2015). Also, group work programmes which have been specifically developed for fathers are rare (Lundahl et al., 2008). Health and social care practitioners, and the Department of Health has recognised the reluctance of fathers to engage in parenting programmes and identified the engagement of fathers into such programmes as a ‘key service target’ (Bayley, Wallace, & Choudhry, 2009).

Positive Impact of Fathers on Child Development and Behaviour

The difficulty in engaging fathers with parenting programmes is something that urgently needs addressed given the significant number of studies which have demonstrated the positive impact that fathers have on their child’s behaviour and development (e.g., school readiness, cognitive development and pro-social behaviours) (e.g., Fabiano, 2007; Berlyn et al., 2008). Even more importantly, it has been shown that, when both parents engage in parenting programmes, the outcomes for children are even more positive (Glynn & Dale, 2015). It has even been found that, compared to mothers, fathers have a greater influence on a child’s misbehaviours (Lundahl, Tollefson, Risser, & Lovejoy, 2008).

Barriers to Fathers Engagement in Parenting Support Services: Recommendations for Best Practice

Bayley and colleagues (2009) carried out a review and a study investigating the barriers which exist to fathers’ engaging with parenting support services. Numerous sources were examined, including published academic peer-reviewed literature, government and community organisation reports and empirical data which was gathered through interviews with nine parenting experts and focus groups and questionnaires with 29 fathers. Barriers identified included: lack of awareness, work commitments, female-orientated services, lack of organisational support and concerns over the content of the programme. Recommendations identified for best practice for fathers included: actively promoting services specifically to fathers as opposed to parents more generally, offering alternative forms of provision, making fathers a priority within organisations and taking different cultural and ethnic perspectives into account. An increased understanding of the perspectives of fathers is crucial to help increase the engagement of father in parenting programmes (Bayley, Wallace, & Choudhry, 2009).

Using data from an online questionnaire, Glynn and Dale (2015) examined the views of social workers regarding about the issues which are impacting on fathers’ decisions to engage in parenting programmes. The findings suggested that participants considered the most important factors which impact of fathers’ participation in parenting programmes include: the qualities of the programme leader, the programme content and the philosophy of the service delivery organisation. The importance of group work/parenting programmes for fathers being specifically tailored for fathers as opposed to simply utilising a generic parenting programme was identified as key by McAllister and colleagues (2012) as the needs of fathers are going to be different from mothers in relation to their parenting.

Mellow Parenting Programmes

Initially developed for use with children under age five years, Mellow Parenting (http://www.mellowparenting.org/) has since, without deviating from the core intervention format, been modified for use with infants (Mellow Babies), antenatally (Mellow Bumps), and with fathers (Mellow Dads). Early years practitioners support Mellow Parenting and Mellow Babies and they are both recommended in United Kingdom national guidelines for evidence-based parenting interventions and the California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare (http:// www.cebc4cw.org/program/mellow-babies/).

Importantly, Mellow Parenting is an intervention which aims to target vulnerable, hard-to-engage families, and in some occasions the collation of explicit consent for anonymised data collection may be significantly challenging. As a result, this leads to an under-representation of the most of needy families in the research literature (Barlow, Smailagic, Ferriter, Bennett, & Jones, 2012; MacBeth, Law, McGowan, Norrie, Thompson, & Wilson, 2015).

One of the key things to highlight with the Mellow Parenting programmes (http://www.mellowparenting.org/) is that they are viewed as a ‘preventative intervention’, helping to prevent the risk of the development of conduct disorders in children (Goldsack & Hall, 2010). The programme attempts to engage parents ‘at the extreme end of the spectrum’ (Puckering, 2004). The fathers that Mellow Dads targets for the intervention are ‘vulnerable’ and typically have complex and numerous problems such as substance misuse, mental health problems and domestic violence. Unemployment, financial difficulties, offending behaviour, poor education and poor literacy are also common in the fathers. Other major parenting programmes including the ‘Incredible Years’ programmes (http://incredibleyears.com/) and the ‘Triple P’ programme (http://www.triplep.net/glo-en/home/) may, despite their effectiveness, be failing to engage the most vulnerable and hard-to-reach families (Puckering, 2004).

Mellow Dads Parenting Programme Piloted in a UK English Prison

One very recent example of one of the Mellow Parenting programmes – Mellow Dads – (http://www.mellowparenting.org/our-programmes/mellow-dads/) targeting of hard-to-reach fathers, Langston (2016) explored the effectiveness of a pilot of Mellow Dads Parenting Programme delivered in a UK prison. The experiences of five men participating in the Mellow Dads Parenting Programme were explored. Findings revealed that the programme facilitators were essential in creating a safe space which enables the participants to freely reflect and consider their past experiences while also acquiring new skills. The participants also found changes in their understanding of themselves, their children and their perceptions of engaging in parenting programmes as a result of taking part in the Mellow Dads programme.

What is Mellow Dads?

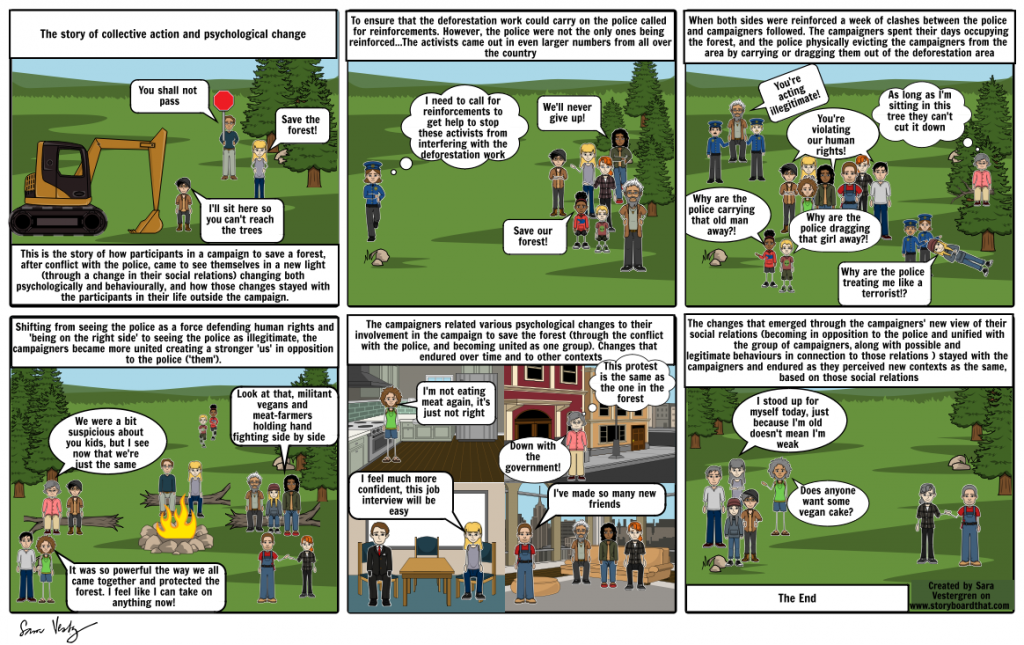

The Mellow Dads intervention comprises of 14 meetings over 14 weeks. Each meetings lasts a full day with the morning focused on topic-based discussion of the fathers’ own lives. Lunchtime is a key element, when fathers meet up with their child and eat lunch together. This is then followed by a play or craft activity. These lunchtimes sessions are considered to be a safe space for the fathers to foster a nurturing relationship with their child. This safe space affords a realistic parenting scenario in which father-child interactions can be observed and filmed for later discussion. The afternoon session includes group feed-back on the father-child videos, including both the filming of lunchtime interactions and videos that were taken in family homes. Fathers and children are separate in this afternoon session (Scourfield, Allely, Coffey, & Yates, 2016).

Working with Fathers of At-risk Children: Insights from a Qualitative Process Evaluation of an Intensive Group-based Intervention

There is sparse research on fathers involved in child welfare cases. However, numerous recent studies have highlighted that there are a number of fathers who do want ‘to be listened to, believed, and given the chance to prove themselves’ (Zanoni, Warburton, Bussey, & McMaugh, 2014:92)

Professor Jonathan Scourfield (University of Cardiff), Dr Clare Allely (University of Salford), Professor Amanda Coffey (Edinburgh Napier University) and Dr Peter Yates (Edinburgh Napier University) (2016) have just published a paper in the journal of ‘Children and Youth Services Review’ which was based on data from a process evaluation of the programme with fathers who attended Mellow Dads which is an intensive ‘dads only’ group-based intervention in order to investigate the challenges of engaging fathers in effective and meaningful family/parenting programmes (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0190740916302699).

The process evaluation, led by Professor Scourfield, included participant observation of one complete Mellow Dads course, interviews with fathers and facilitators, interviews with the intervention author and a study of programme documentation. As mentioned earlier, the Mellow Dads programmes is aimed at fathers with children under five years of age. Also fathers where there are confirmed child protection issues or families which are considered to be at risk.

The process evaluation was interested in examining a number of areas including: the theoretical underpinning of the programme, the acceptability of the programme to the fathers and the challenges experienced by the facilitators in delivering the Mellow Dads programme. Fathers reported that they appreciated the efforts of facilitators to make the group work, they valued the advice on play and parenting style and also valued the opportunity to talk to fathers who are also experiencing similar problems. The process evaluation did reveal a number of barriers which had an adverse impact on the effectiveness of the Mellow Dads programme. For instance, one of the barriers was the significant time it took to get the fathers to attend the programme in the first instance and then to maintain their engagement with the programme, the limited practice of parenting skills with fathers who were not living with their children and the difficulties father experienced in sharing personal information in the group.

The obstacles identified in this process evaluation “raises the question about how much change can be expected from vulnerable fathers and whether programmes designed for mothers can be applied to fathers with little adaptation” (Scourfield, Allely, Coffey, & Yates, 2016: 259).

Overall, if one is to successfully meet the needs of fathers seeking to develop their relationship with their children and to develop their role as fathers, it is unhelpful for parenting programmes to be gender blind (McAllister et al., 2012; Jenkinson, Casey, Monahan, & Magee, 2016).

Link to article: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0190740916302699

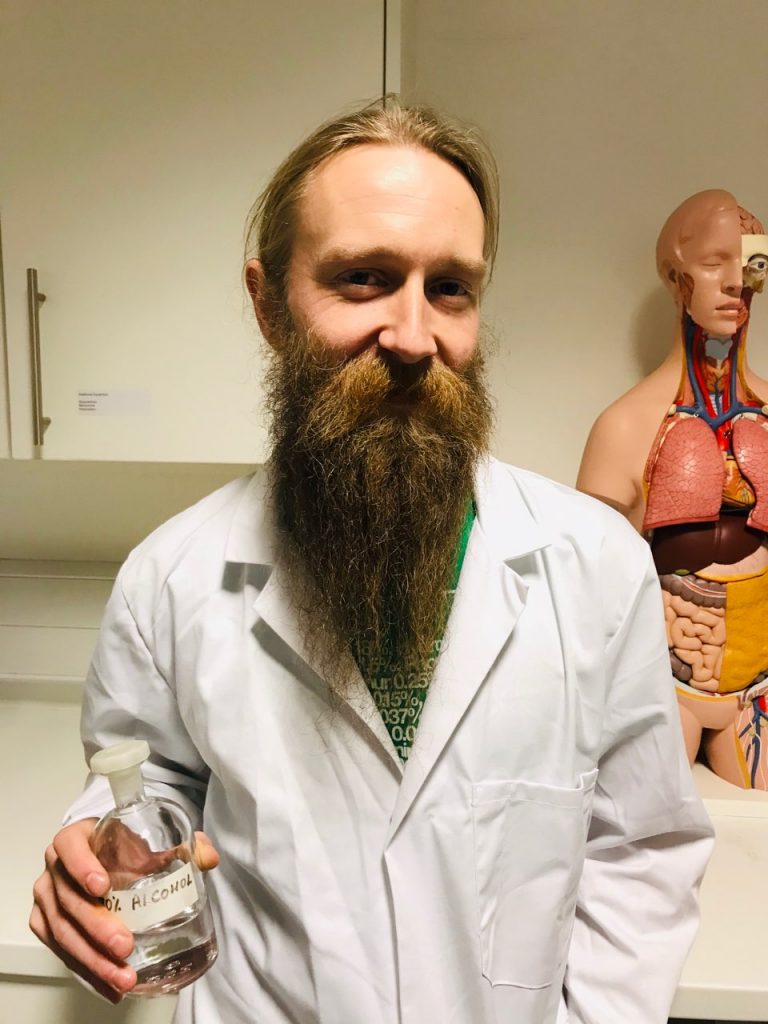

Dr Clare Allely

Lecturer in Psychology, University of Salford

Affiliate member of the Gillberg Neuropsychiatry Centre. University of Gothenburg.

References

Barlow, J., Bergman, H., Kornør, H., Wei, Y., & Bennett, C. (2016). Group‐based parent training programmes for improving emotional and behavioural adjustment in young children. The Cochrane Library.

Bayley, J., Wallace, L. M., & Choudhry, K. (2009). Fathers and parenting programmes: barriers and best practice. Community Practitioner, 82(4), 28-32.

Berlyn, C., Wise, S., & Soriano, G. (2008). Engaging fathers in child and family services. Family Matters, 80, 37-42.

Fabiano, G. A. (2007). Father participation in behavioral parent training for ADHD: Review and recommendations for increasing inclusion and engagement. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(4), 683-693.

Glynn, L., & Dale, M. (2015). Engaging dads: Enhancing support for fathers through parenting programmes. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 27(1/2), 59.

Jenkinson, H., Casey, D., Monahan, L., & Magee, D. (2016). Just for Dads: a groupwork programme for fathers.

Langston, J. (2016). Invisible fathers: Exploring an integrated approach to supporting fathers through the Mellow Dads Parenting Programme piloted in a UK prison. Journal of Integrated Care, 24(4), 176-187.

Lundahl, B. W., Tollefson, D., Risser, H., & Lovejoy, M. C. (2008). A meta-analysis of father involvement in parent training. Research on Social Work Practice, 18(2), 97-106.

MacBeth, A., Law, J., McGowan, I., Norrie, J., Thompson, L., & Wilson, P. (2015). Mellow Parenting: systematic review and meta‐analysis of an intervention to promote sensitive parenting. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 57(12), 1119-1128.

McAllister, F., Burgess, A., Kato, J. and Barker, G., (2012) Fatherhood: Parenting Programmes and Policy – a Critical Review of Best Practice. London/Washington D.C.: Fatherhood Institute/ Promundo/MenCare.

Panter – Brick, C., Burgess, A., Eggerman, M., McAllister, F., Pruett, K., and Leckman, J.F. (2014) Practitioner review: ‘Engaging fathers – recommendations for a game change in parenting interventions based on a systematic review of the global evidence’. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2014 Nov; 55(11): 1187-212.

Puckering, C. (2004). Mellow parenting: An intensive intervention to change relationships. The Signal, Newsletter of the World Association for Infant Mental Health, 12(1), 1–5 (January–March 2004).

Salinas, A., Smith, J. C., & Armstrong, K. (2011). Engaging fathers in behavioral parent training: Listening to fathers’ voices. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 26(4), 304-311.

Scourfield, J., Allely, C., Coffey, A., & Yates, P. (2016). Working with fathers of at-risk children: insights from a qualitative process evaluation of an intensive group-based intervention. Children and Youth Services Review, 69, 259-267.

Zanoni, L., Warburton, W., Bussey, K., & McMaugh, A. (2014). Are all fathers in child protection families uncommitted, uninvolved and unable to change?. Children and Youth Services Review, 41, 83-94.