By Ivett Ayodele

Myths and recent discoveries about Psychology’s most famous Case Study

A few days ago I was reading the August issue of the BPS Digest and came across a piece by Christian Jarrett titled “What textbooks don’t tell you about psychology’s most famous case study” (See this article here.) I was surprised because as far as I was concerned, the story of Phineas Gage always sounded more like a myth to me. I was compelled to do some research on the new discoveries and here is my own summary about the real story of Phineas Gage.

If you are studying Psychology or have an interest in it, you have probably heard of the case of Phineas Gage. His story is remarkable and very popular among psychology students all over the world (Jarrett, 2015).

Who was Phineas Gage?

Phineas Gage was a railway worker in the 1800s. On the 13th September, 1848 he suffered a traumatic brain injury when an iron rod went through his entire skull, destroying a large section of his brain (Cherry, 2015). The fact, that he not only survived but was also able to speak and walk after the accident, made him one of the most famous patients in neuroscience (Jarrett, 2015). However, according to Griggs (2015), most textbooks (at least the American ones) give a misleading account of his story. In particular many suggest he had a dramatic change in character and personality.

“In this regard his mind was radically changed, so decidedly that his friends and acquaintances said he was “no longer Gage”. (Harlow, 1868, p. 340)

The Myth

Richard Griggs, Emeritus Professor of Psychology at the University of Florida, analysed the content of 23 textbooks and found that most of them had told the story of Phineas Gage inaccurately (Jarrett, 2015).

These textbooks will tell you that although Phineas Gage survived the accident, he became a changed man (Cherry, 2015), he never worked again or that he became a circus freak for the rest of his life, showing off the holes in his head (Jarrett, 2015). However, according to Griggs (2015), the most appalling error seems to be that Gage survived for 20 years with the tamping iron rod embedded in his head!

New Discoveries

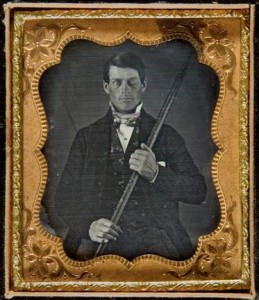

Thanks to the work of Malcom Macmillan and Mathew L. Lena, who carried out some historical analysis between 2000 and 2010 (e.g. see “Rehabilitating Phineas Gage”, 2010), it seems that in fact, Phineas Gage made a surprisingly good recovery. He ultimately emigrated to Chile and became a coach driver, controlling six horses and dealing politely with non-English speaking passengers (Jarrett, 2015). Furthermore, in 2008, some new photographic evidence emerged from Jack and Beverly Wilgus. They acquired the daguerreotype below, of which this is a photograph 30 years ago, but it was not identified as Phineas Gage until 2008. (Macmillan & Lena, 2010).

Source: https://www.uakron.edu/gage/adaptation.dot

According to Macmillan and Lena (2010) two relatives of Phineas Gage also have copies of the photograph of a similar daguerreotype, which was passed down to the descendants of Phineas’ siblings. They therefore argue, that there is no doubt the image is of Phineas.

There is further evidence by Macmillan and Lena (2010) that suggests, that Phineas Gage not only recovered after his accident but also consistently sought to readapt to his circumstances.

- Phineas returned to work on his family farm just four month after his accident and sought his old job four months later.

- Two or three years later, he started lecturing and exhibiting himself, advertising and traveling independently, requiring him to re-learn any lost social skills.

- He worked as a Currier for a year (1851-1852) and he also learnt how to drive a coach during this period.

- He was reliable enough to be employed as a Coach driver in Chile, where he remained for about 7 years; using complex social and cognitive-motor skills which were required for this job.

- He was able to adapt to the language and custom of Chile, which was a foreign land for him.

- A doctor who knew him well in Chile stated that he saw “no impairment whatever” in him after a certain period of time.

In his late years, Phineas Gage began to suffer from ill health and decided to follow those members of his family, who had relocated to San Francisco, California. He eventually regained his health and worked as a farmer in Santa Clara. (Cherry, 2015). However, he soon started to experience convulsions and became dissatisfied with his job, changing his employer frequently before deciding to return to his family in San Francisco. He died of a series of severe convulsions on the 21st May 1860 (Macmillan & Lena, 2010.)

Why is it important to set the record straight about Phineas Gage?

Well, according to Griggs (2015) there are one and half million students studying Psychology in the USA alone and they are introduced to the discipline via textbooks (Jarrett, 2015).

Therefore, “it is important to the psychological teaching community to identify inaccuracies in our textbooks so that they can be corrected, and we as textbook authors and teachers do not continue to “give away” false information about our discipline” (Griggs, 2015).

I hope you enjoyed this post and I would like to invite you to submit a piece of your own to our Blog! You can write about you experiences at Salford or if you read a good book, or see a good film you could write a review on that! For more information please contact me on i.b.ayodele@edu.salford.ac.uk.

References

Cherry, K. (2015, November 18). About Education. Retrieved from psychology.about.com: http://psychology.about.com/od/historyofpsychology/a/phineas-gage.htm

Griggs, R. (2015). Coverage of the Phineas Gage Story in Introductory Psychology Textbooks: Was Gage No Longer Gage? Teaching of Psychology, 195-202.

Harlow, J. M. (1868). Recovery from the passage of an iron bar through the head. Publications of the Massachusetts Medical Society, 2, 327–347, [Facsimile in Macmillan, 2000,

Jarrett, C. (2015). What the textbooks don’t tell you about psychology’s most famous case study. BPS Digest, 626.

Macmillan, M., & Lena, M. L. (2010). Rehabilitating Phineas Gage. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 641-658.