It’s almost that time of year again.

I saw my first Christmas display last week – admittedly in a pub, and advertising Christmas bookings, but it still kicked off that wave of panic that I haven’t exactly prepared (at all) for Christmas yet.

The presents, the food, the drink, the parties… and the day’s after.

I obviously can’t speak for everybody, with drinking becoming less common (Fat, Shelton & Cable, 2018; Oldham, Holmes Whitaker, Fairbrother & Curtis, 2018), but I’m quite partial to an alcoholic beverage, and the festive period always seems to come with an increased number of events at which we’re encouraged to ‘get a bit festive’.

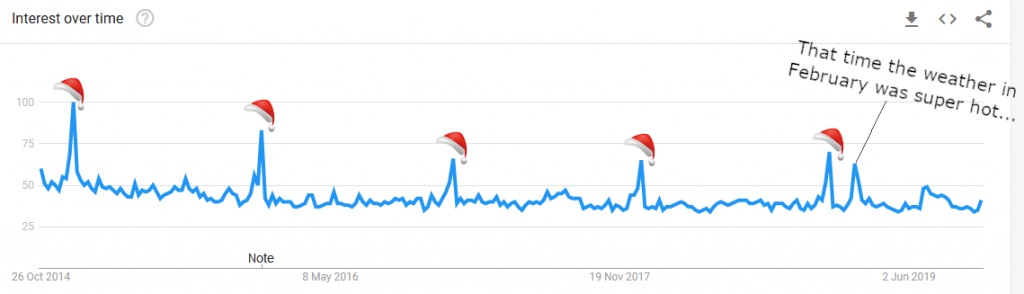

The following day often comes with aches, pains, miserableness, and an inability (or perhaps lack of willingness) to get anything done. Most people would know this experience as a ‘hangover’, and it seems to be a pretty common experience, particularly at this time of year. Google trends shows consistent worldwide peaks in searches including the term hangover at the end of the year (with the maximum number of searches occurring roughly around New Years Eve).

Your hangover might not, however, be all about how much you drink, or even your choice of festive tipple.

Obviously, we don’t get a hangover if we haven’t been drinking, but people have long wondered why the experience of hangover seems to be so variable – take for example P. G. Wodehouse’s categories of hangover (referred to in the novel ‘The Mating Season’, from 1949).

“I am told by those who know that there are six varieties of hangover – the broken compass, the sewing machine, the comet, the atomic, the cement mixer, and the gremlin boogie, and his manner suggested that he had got them all.”

Recently, we’ve conducted research at the University of Salford that has suggested this variety in the hangover experience may be due to your psychology, as well as your biology.

In our research, 86 participants were asked to rate the severity of their hangover, as well as 8 individual symptoms commonly associated with hangover (Thirsty, Tired, headache, dizzy/faint, loss of appetite, stomach ache, nausea, and heart racing). Participants also completed questions that measured a kind of ‘psychological coping mechanism’, that is, a way that we psychologically influence our experience of pain, discomfort, or stress.

Specifically, researchers asked participants to indicate how much they tended to ‘catastrophize’ in response to pain – People who catastrophize tend to magnify or exaggerate the seriousness of pain, for example they might think that ‘it’s only going to get worse’, or that they ‘can’t stand this much longer’.

Results suggested that the more people catastrophized, the worse they reported their last hangover was, even when controlling for participants peak blood alcohol concentration (a measure of how much someone has drunk).

These results are interesting because of the role that coping mechanisms, like catastrophizing, seem to play in longer term health outcomes such as depression, and addiction (Bendall & Royle, 2018; Yang 2018). Catastrophizing has itself been associated with craving (a powerful urge or desire to consume a drug), a key criterion in addiction (Martel, Jamison, Wasan, & Edwards, 2014).

All together, this might suggest that coping mechanisms play a role in both hangover, and the development of addiction in those who are predisposed (due to biological factors like genetics). If this is the case, then the experience of hangover might act as a predictor of future risk for addiction, and help healthcare professionals to target interventions that help prevent addiction in the first place.

So understanding hangover might help with more than just your headache.

References

Bendall, R. C., & Royle, S. (2018). Decentering mediates the relationship between vmPFC activation during a stressor and positive emotion during stress recovery. Journal of neurophysiology, 120(5), 2379-2382.

Fat, L. N., Shelton, N., & Cable, N. (2018). Investigating the growing trend of non-drinking among young people; analysis of repeated cross-sectional surveys in England 2005–2015. BMC public health, 18(1), 1090.

Martel, M. O., Jamison, R. N., Wasan, A. D., & Edwards, R. R. (2014). The association between catastrophizing and craving in patients with chronic pain prescribed opioid therapy: a preliminary analysis. Pain Medicine, 15(10), 1757-1764.

Oldham, M., Holmes, J., Whitaker, V., Fairbrother, H., & Curtis, P. (2018). Youth drinking in decline.

Yang, X., Garcia, K. M., Jung, Y., Whitlow, C. T., McRae, K., & Waugh, C. E. (2018). vmPFC activation during a stressor predicts positive emotions during stress recovery. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience, 13(3), 256-268.

Sam Royle is a Psychology Technician and PhD student at the University of Salford.